November 2024 Issue Available At All Leading Newsagents!

Read the featured article from this month’s issue below

Gilgunnia Gold

by John ‘Nugget’ Campbell

The former gold mining town of Gilgunnia, NSW, is 110km south of Cobar and 146km north of Hillston, but not much exists there today. There’s a rest area with a small historical mining display and some local history information on the rest stop sign, and that’s about it. Most likely because it was at the intersection of three major roads and on a travelling stock route, the Gilgunnia Hotel was established there in 1873 by Mr and Mrs Kruge, and things moved along at a typical outback pace until small amounts of alluvial gold were found in the area around 1887. This didn’t cause too much excitement but the discovery was enough to fire the imaginations of a few serious prospectors and eventually the first payable reef gold was discovered by John “Jackey” Owen in 1895. He went on to discover other notable mineral fields. By June 1895 there were about 450 men on the field with 17 claims on payable gold. There was good gold showing in the reefs and by October there were a number of mines operating including the No.1 North; No.2 West; the Hand in Hand; The Off Chance; Riley’s; the Mount Allen Syndicate; the Rising Sun; The Dream (later to become Her Dream); the FourMile; Keep It Dark; Australian Natives; Tarcombe; The Welcome, White Reef; and Talbot and Cranes. No.1 North and Australian Natives were the deepest at 100 feet and still showing good gold.

Above: John ‘Jackey’ Owen, discoverer of the first payable reef at Gilgunnia

By November 1895 the miners were calling for a battery to be erected and some of the ore was extremely rich, with one mine sending six tons of ore to the Clyde works in Sydney for a yield of seven ounces per ton. A report in June 1896 noted that the lack of water had held up mining but rains had recently filled the tanks; it also noted that the much-needed battery was being constructed and that there were at least 1,000 tons of stone waiting to be crushed. In the same month, one troubled miner suicided by putting a stick of Rackarock (explosive consisting of potassium chlorate and nitrobenzene) with a slow fuse and detonator into his mouth and lighting it. The papers noted that this wasn’t uncommon on mining fields. On the 28th of July the first battery was officially declared open with Mr Maschwitz being the proprietor, and a celebratory ball was held in the evening. Most crushings ended up yielding about an ounce of gold per ton but in 1897 the Her Dream Mine was an exception when, in December, it treated 51 tons for just over 106oz of gold. It had produced 666oz of gold from its last five crushings and paid a dividend of five guineas per share, there being some 80 shares in the venture. The town of Gilgunnia was declared in 1897 and this pretty much coincided with its peak population of 1,000 residents who were serviced by a court house, police station, school, several general stores, three pubs, a billiards hall, a dance hall and various other retail establishments. There was no mention of a church. By 1898 the newspapers had lost a lot of interest in the field but reported that crushings of an ounce per ton were still the average, with the Her Dream Mine usually producing a slightly better yield. Water was still a problem – either a lack of it or too much courtesy of torrential rain.

The Royal Hotel closed in 1898 leaving thirst-quenching duties to Tattersalls and The Commercial. In September of that year another miner became deranged, first threatening his family and then cutting his own throat. It was not clear if he passed away but it was noted that he was the son of the miner who had suicided in 1896. The total gold yield for the field in 1898 was just over 628oz with Her Dream (sometimes called The Dream) accounting for more than 375oz. At the other end of the scale the Hidden Treasure lived up to the negative connotations of its name and produced one solitary ounce of gold for the entire year. By the middle of 1899 the battery was out of commission waiting for the arrival of new shoes and dies. Some mines were now down to the 180-foot level without rich ore being discovered. On April 6th, Ah Clun, one of the Chinese market gardeners who supplied the town with vegetables grown at Boggy Tank, was found almost dead with multiple cuts, bruises and broken bones. It was claimed his mate, Ah Pling, had tried to murder him with an axe, rod and slasher. Ah Clun was conveyed to the pub then on to Nymagee Hospital. Constable Macpherson covered a lot of ground and eventually tracked down the culprit and arrested him on the road to Nymagee. In December 1899, Her Dream crushed 85 tons for a fabulous return of 603oz of gold.

The Tattersalls Hotel, Gilgunnia, 1922. It later became the post office but by then Gilgunnia was more of a reference point on a map than an actual town

A year later several mines had closed and some were on tribute but Her Dream was still the standout mine and was now down to 200 feet. In early December 1900 it crushed 50 tons for 107oz and later that same month, 141 tons for 262oz of gold. The entire gold output for the field in 1901 was 927oz from 431 tons however 273 ounces of that came from Her Dream’s December crushing of 150 tons. An earlier crushing in August had yielded more than 8oz to the ton so it is clear that most of the other mines still operating were on their last legs. During the year the Gilgunnia Battery Company had erected two 60-ton cyanide vats to treat the tailings and it was hoped that this plant would help the profitability of existing mines. By now the town had shrunk to one pub, a post office, the police station, two small general stores, a butcher, a few scattered mostly empty houses and the battery. The battery and cyaniding plant were eventually sold to Her Dream in August 1902. Most mines, including Her Dream, were still averaging about one ounce to the ton but in October, Seigal and Sons at the Last Chance, produced nearly 69oz from 17 tons. In July 1905, Mr Helm, the much admired school headmaster who had started the school in January 1896, was promoted and posted to Blayney. Although there were still 18 pupils attending the school, a new teacher, Mr F. Bisley, wasn’t appointed until July 1907 but he didn’t accept the posting and the school closed the same month. Mining struggled along until 1907 when the Her Dream Mine and also the battery and cyaniding plant it owned, went into liquidation. The mine hadn’t been profitable for two years and was down to the 260-foot level. In 1913 Mr Wallace obtained the Her Dream mine with high hopes of making his fortune but water in the mine proved his undoing.

In 1915 a Cobar syndicate tried to dewater Her Dream. This was the only work being carried out on the field and it ultimately proved unsuccessful. In 1917 another local syndicate tried to get Her Dream back up and running and struggled with the water problem into 1918, to no avail. As for the town, the only decent building still standing was Tattersalls Hotel, the police station having been “abolished” in December 1915. The years rolled by until Mr A. Hodge, with more hope than good sense, assumed ownership of Her Dream in 1936 and had two men install 200 feet of ladders. Fortune did not favour him. In 1939, Her Dream’s charms managed to attract the Seigal Brothers who laboured through until the end of 1940 for little or no result. Since the Second World War the only activity on the field was an open cut operation that started back in the early 1990s but it came to nothing. The town of Gilgunnia and the mines that feasted on its reefs fended off droughts, fires, the Spanish Flu epidemic, heatwaves, duststorms, frost and grasshopper plagues but couldn’t survive when water was struck at depth and gold at depth was too expensive to mine.

MINER BLOWS HIS HEAD OFF

Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal Friday, 12th June, 1896

At the Four Mile, near Gilgunnia goldfield, on Wednesday morning, a miner named McLaughlin committed suicide in a most determined manner. About 7.30am, a miner named Talbott, whose camp is distant some 30 yards from that of McLaughlin, was aroused by a loud report, but owing to the dense fog prevailing at the time could not locate the direction. About half-an-hour later, however, he went to McLaughlin’s tent and was horrified to find the deceased lying on bis back on his bed with the whole of his face and front portion of his head blown away, and the brain exposed. Portions of the brain and parts of the skull, teeth, and beard were lying scattered around the bed, floor, and side of the tent. Pieces of bone and beard were also scattered outside the tent from the force of the explosion. Rackarock was evidently the means employed to effect his purpose. Half a plug of the explosive was missing from the Moonlight claim on which McLaughlin’s claim was situated, and also a short piece of fuse which he must have secured on Tuesday night or very early on Wednesday morning. The explosive he evidently placed in his mouth with the detonator and fuse attached. The facts at present disclose no reason for the rash act. At 8 o’clock on Tuesday evening McLaughlin appeared to be in his usual spirits, and was conversing rationally and cheerfully. He was at one time proprietor of an hotel in Bourke, and was well liked and respected. It is thought that his financial troubles may have affected his reason. The body has been brought into town. An inquest will be held.

Echoes from the past

A FORTUNATE FIND

Sydney Morning Herald

16th July, 1934

A family passing through Mudgee had a fortunate find. They camped on pipeclay, about four miles from Mudgee, and the father started prospecting among the old mining workings, with no results, until his little son, who had been playing on an old mullock heap, scratched the surface and picked up a gold nugget which was found to weight seven ounces. Can you imagine the scene. The boy probably called out, “Is this what you’re looking for Dad?”

WEDDERBURN GOLD RUSH

Sydney Morning Herald

22nd March, 1950

The new Wedderburn gold rush is on in earnest with prospectors coming from all parts of Victoria. After a meeting of the shire council this afternoon, the shire secretary, Mr A. E. Cooper, said: “We will grant as many claims as possible to people wanting to dig the streets, provided the earth is put back in its position. Gold is better out of the ground that in it. It has reached a stage where it is open go.” “We’ll dig up the whole town,” one resident said. Thirty claims have been pegged in Wilson Street – the main road through the town. Claims have also been pegged in Reef Street, off Wilson Street, by people who like the sound of the name. Backyard mining is also on in full swing today. The local publican, Mr R. Baker, and his barmen, spent more time in the mine at the back of the hotel than in the bar. No big find was reported today – only several pieces weighing two or three pennyweights and some specks.

SEARCH FOR A LOST REEF

Sydney Morning Herald

28th March, 1952

Mr Leslie Hall, 56, a bachelor, found a gold nugget valued at £500 six inches below the surface of Wilson Street, Wedderburn, today. He was sinking a shaft when his pick brought up the nugget. It weighed 27 ounces. The place is opposite the home of Mr David Butterick who has dug up a £10,000 fortune from his backyard gold mine. Mr Hall recently took over the claim of another prospector, former greengrocer Albert Smith, who dug up a £1,100 nugget from the spot two years ago, and retired six months ago. He hopes to find a gold reef which old residents of Wedderburn believe runs under Wilson Street. An Italian named Cerchi found the reef during the gold rush last century but it was lost.

FLOODED WITH SPECKS OF GOLD

Sydney Morning Herald

22nd June, 1952

This week’s floods caused an avalanche at Walhalla (population 400) ghost mining town 125 miles east of Melbourne, and poured tons of gold-flecked rock and mud into the streets. Disregarding their wrecked homes, some old prospectors are busy washing paydirt. They predict new prosperity for the township, through which, last century, £10,000,000 of gold passed. But Walhalla faces a new peril before it can think of gold. Waters from Stringer’s Creek are running wildly through the town. Melbourne is rushing pipes and other equipment and teams of men are trying to save Walhalla from its third swift flooding in a week. The first flood cut Walhalla off from the rest of Victoria early this week and no word of the township’s ordeal came to the outside world until yesterday. Water rushed down from the hills carrying a great mass of mullock that had been stacked outside old diggings. Then came an avalanche, a huge landslide from the soaked and crumbling hills. And the gold. There is a glint in the miners’ eyes as they pile up flood defences. They are dreaming of the old Walhalla and its 14 hotels, flashing wealth and thousands of people.

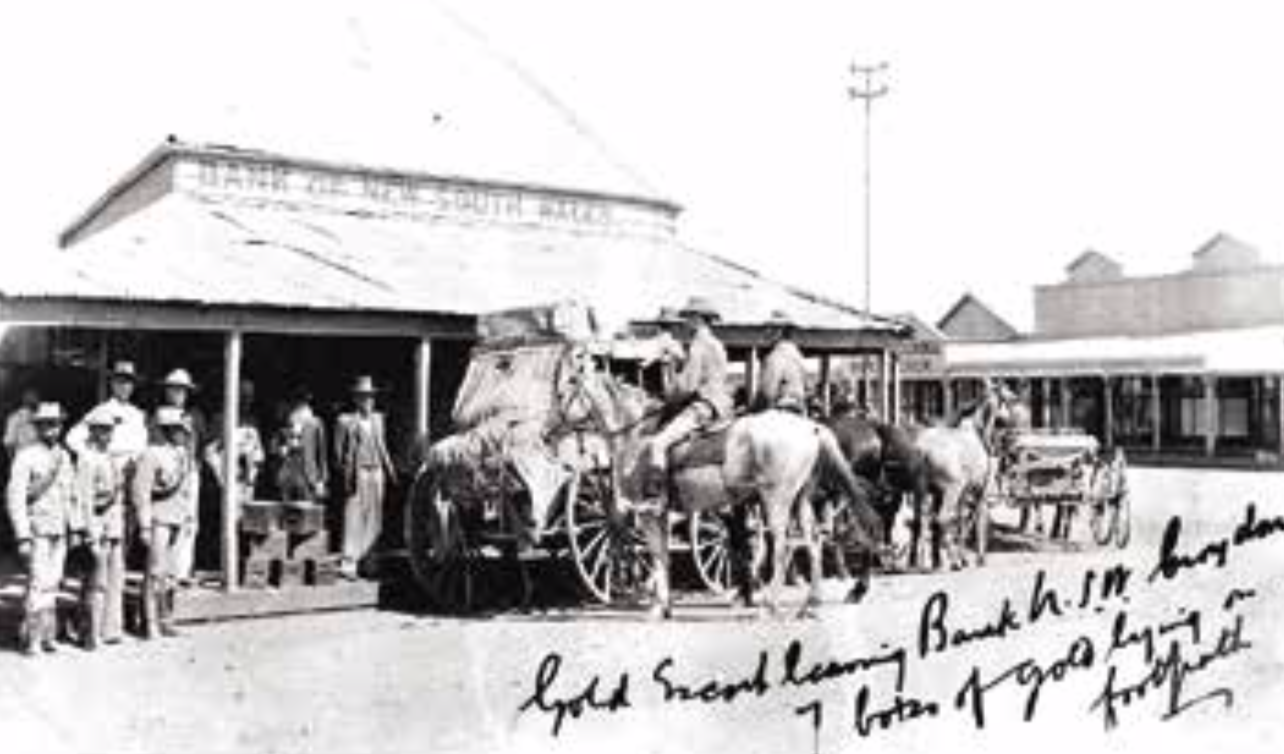

THE GOLD ESCORT ROBBERY

The Herald (Melbourne)

18th July, 1953

It was 100 years ago that a band of desperate bushrangers huddled beside dim lights on the Heathcote goldfields and planned the daring robbery that led three to the gallows of the old Melbourne gaol in Russell Street. The gold they stole was then worth £10,000 and most of it was never found. According to the legends of the hills, the treasure is still believed to be buried in the scrub near Heathcote, once known as McIvor. The weekly gold escort jogged out of this prosperous mining town for Kyneton and Melbourne about 9am on July 20, 1853. In the coach, behind the driver Thomas Fookes, were 46 packages containing 2,323 ounces of gold and nearly £1,000 in cash. Around the coach rode Superintendent Warner, Sergeant Duins and troopers Davis, Morton and Reiswetter. The troopers trotted about 14 miles from McIvor, came to a sharp bend in the road and slowed when they saw a strange palisade of gum tree trunks and branches on a rise beside the dusty track.

Before the suspicious troopers could fumble for their heavy pistols, “a murderous fire was poured on them from the palisade above.” Fookes fell from the coach with a bullet through his knee and a gash across his temple. Morton collapsed with a severe shoulder wound, Reiswetter with a ball in his leg, and Davis with another through his cheeks. Duins, his horse wounded twice, fired his pistol at the bushrangers and galloped off to McIvor for help as Warner rode into the scrub to try to attack the ambushers from a flank.

The wounded men were still groaning on the ground as six bushrangers, wearing heavy guernseys, rifled the coach and thundered into the bush to measure out the gold with powder flasks. By nightfall, when the wounded men had been rescued, about 400 miners and volunteer special constables were searching the bush. But while the searching continued, some of the bushrangers had reached Collingwood and other districts and were trying to board ships listed for Mauritius and other ports. By August 4, rewards offered for the capture of the bushrangers totalled £2,900, one of the biggest in Victorian history. Inquiries were at a dead end when one of the bushrangers, George Francis, suddenly turned informer and gave detectives information that led to the arrest of three men. Soon afterwards, he escaped from his escort and committed suicide. But by then the police were sure they still had two men to find. One – his name was Grey – was never traced. The other, when captured, said his name was John Francis, brother of the dead bushranger, and was willing to turn Queen’s evidence in return for a free pardon.

John Francis received his pardon and was the chief Crown witness on Saturday, September 17, 1853, when George Melville, George Wilson and William Atkins appeared on charges of robbery under arms. The three prisoners were tried, found guilty and hanged but police admitted that they had recovered less than £1,000 worth of the gold. What happened to the bulk of the gold, which today would be worth about £35,000? (Ed. More than $5 million these days). Was it taken from a cache by Grey, the man who was never caught? Was it passed to friends of the condemned men before the police surprised them?

Or is it – as many old bushmen believe – still hidden in the earth near Heathcote from which it was mined 100 years ago?

GOLD BUYER DUPED

Bendigo Advertiser

18th January, 1906

Two men, William Sherwin and Benjamin Evans, were arrested today at Fremantle on a charge of false pretences. It is alleged that the two men are connected with a case of imposition reported recently to the Kalgoorlie detective office. About six months ago Sherwin arrived in Kalgoorlie, and, knowing something about his past activities, the police kept him under surveillance. Four months ago the other man, Evans, came to the district, and almost immediately started betting. Concurrently with the arrival of Evans in Kalgoorlie, Sherwin made the acquaintance of a Boulder resident, Oliver William Osmond, and, posing as a well- informed racing tipster, he occasionally gave his newly-found friend tips.

It is alleged that about a week ago, Sherwin told Osmond, as a great secret, that he (Sherwin) had a brother working as an assayer in one of the big mines, and that his brother had a large quantity of gold to dispose of. The upshot of the conversation was that Osmond agreed to buy the gold himself at a very attractive price. On Thursday last, Osmond met Sherwin and his alleged brother, who was none other than Evans, by appointment. At this interview another meeting was arranged for at 3 o’clock on the following day, when Sherwin and Evans stated that they would have bar gold to the value of £500 with them. The trio met at the appointed time, and Osmond then handed £250 in cash and a post-dated cheque for a smaller amount to Sherwin and Evans, and received what was apparently three 100oz bars of gold in exchange. The sellers of the gold bricks wanted Osmond to pay the full amount in cash, but Osmond declined to do so until he had the bricks assayed. The buyer and the sellers then parted.

Later in the day Osmond, suspecting that he had been duped, chopped one of the bars in two, and found to his sorrow that what he had bought for gold was only copper covered over with gold leaf. He at once communicated with the local detectives and they satisfied themselves as to the identity of the men wanted, and telegraphed the information to Perth, with the result that Sherwin and Evans were arrested at Fremantle today.

FLOGGED FOR FINDING GOLD

The World’s News (Sydney)

11th August, 1951

A convict was triced up for a flogging in Berrima gaol – back bare, hands lashed to rings in the wall above his head, feet manacled.

The lash fell – 60 strokes. And what was this convict’s crime? He had found gold, picked up grains of the precious metal and hidden them in his clothes. Maybe a mate gave him away, for to find gold was a crime in those days. The authorities believed if a gold rush came, every warder would go and leave the prisoners to escape. This was in 1825. The point arises. Why did the convict even look for gold? He must have heard about it being found, and he had.

As far back as 1814, when the road was being built across the Blue Mountains, a gang found large quantities of gold. This was reported to the engineer in charge. He ordered them to keep it secret on pain of being flogged. They had all been promised a pardon when the road was finished, so they kept quiet. The next report came in 1823 when assistant-surveyor James McBrian found gold on the Fish River, 15 miles from Bathurst. In his field book, now preserved in Sydney, he reported, “At eight chains 50 links to river and marked gum tree, found numerous particles of gold in the sand and in the hills convenient to the river.”

Again, in 1830, gold with pyrites, was found in Vale of Clywdd in the Blue Mountains. The discoverer was the Polish scientist Count Strezlecki, who later named Mount Kosciusko. At the urgent request of the Government, he did not make his find public. But 11 years later, an experienced geologist, Rev. W. B. Clarke found gold in the Macquarie Valley, and also at Vale of Clywdd.

Clarke had come to New South Wales “to take charge” of King’s School at Parramatta. His essays on science were the basis for study of such subjects in New South Wales. Without having heard of Strezlecki’s find at Vale of Clywdd, Clarke found gold there and later in the valley of the Macquarie River, near Bathurst. That was in 1844, when the State was reaching out in commerce and trade and barriers were being broken down. Clarke had been in Russia, then practically the only gold- producing country in the world. In 1847, comparing Australia with Russia, he said, “New South Wales will probably on some future day be found wonderfully rich in minerals.”

In the Maitland Mercury of January 31, 1849, he wrote, “It is well known that a gold mine is certain ruin to its first workers, and in the long run gold washing will be found more suitable for slaves than British freemen.”

Incidentally, at that time British freemen were swarming across the Pacific to the Californian fields. Among them was Edward Hammond Hargreaves, who in 1851, found gold at Summer Hill Creek near Bathurst. This was done on his hurried return, after observing that the country, where gold was won in California, resembled the land near Bathurst. He was right; but he was far from being the first man to find gold in Australia. Under any system but a convict one, Australia would have leaped ahead when the road was made over the mountains in 1814 and gold found there. But that is how history is made. The real discoverers never get the credit.

Coolgardie – The rush that saved the west

By John Drain

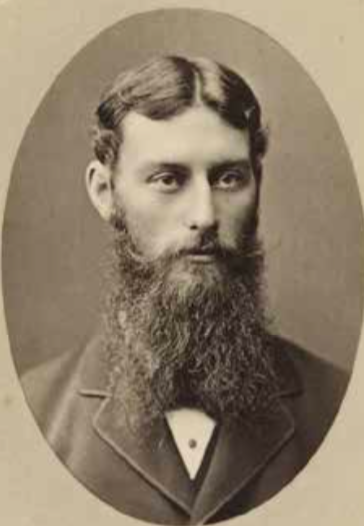

Arthur Wellesley Bayley and William Ford are accredited with finding the first gold at Coolgardie on September 13th, 1892, however, controversy has existed over the years as to who were the rightful discoverers. The pair were granted the reward claim on 17th September.

Nothing I have ever read on the matter actually attempts to discredit the partners in the finding of the reef or their subsequent sale of it, but there is ample evidence to suggest they may not have been the first to find gold in the vicinity.

Probably the earliest reference to gold believed found in the general area of that part of the country, later to be known as Coolgardie, is reported in the journals of Charles C. Hunt, a surveyor employed by the Western Australian Government to search for and find pastoral country suitable for grazing stock. This work was carried out to the east of the town of York and spread into the goldfield, now known as Hampton Plain, between the years 1864 and 1866. Hunt’s commission also required him to establish watering points such as soaks and wells to enable those who might follow to be able to sustain themselves. For this purpose, he was supplied with several convicts who were to do the manual work, and several pensioner soldiers as guards.

William Ford, c.1900

When they were well into the eastern goldfields the convicts took it into their heads to grab some of the horses and food, and set off overland to make their escape to South Australia. Not being experienced bushmen and probably weakened by the hard work of digging wells, together with a poor staple diet, the convicts were soon overtaken by Hunt’s soldiers. On being returned to camp they were found to be in possession of a small quantity of gold. It seems their wanderings were such and their navigation so poor they were not able to lead Hunt’s party to the spot where the gold was found. It’s likely of course, they may simply have been playing dumb as many do about the whereabouts of gold.

Bayley and Ford first met in Croydon, Queensland, when each was prospecting there. After the Croydon gold ran out, they separated, with Bayley moving to Southern Cross where gold had been discovered in 1888 and which, at the time, was the most eastern field being worked in Western Australia.

One night while Bayley was resting from his work with a mining syndicate, Gilles McPherson, a well-known prospector in the Yilgarn district, staggered into Bayley’s tent having suffered a terrible perish due to the shortage of water. McPherson, a hardy Scotsman, was in a bad way and it took several days nursing on the part of Bayley before he recovered sufficiently to make much sense. He showed Bayley some gold he had found to the east and south that seemed to fit in with the direction from which McPherson had come from Lake Lefroy. McPherson went to great lengths to impress on Bayley the fact that there was some gold out there but also emphasised the terrible shortage of water. Perhaps fired by McPherson’s enthusiasm for prospecting, or simply disenchanted with working for wages, Bayley threw up the job and set off to Nullagine some 1,200 kilometres to the northwest in the Pilbara Goldfield.

Bayley and Ford photographed after being granted the reward claim.

Nullagine produced a lot of alluvial gold between the township and as far east as Mosquito Creek. Bayley found some gold but after a time shifted 200 kilometres south to Top Camp on the Ashburton field. Here he joined with noted prospector Tom Kegney as sharing mates and during their time together they had the good fortune to find a handsome amount of gold, including one 68-ounce nugget. Never short of a solution to a problem, Bayley promptly chopped the nugget in half so each might have his share.

Hearing of rich gold at Nickol River to the north, Bayley decided to try his luck there. The field was along the tidal sea- shore and could only be worked while the tide was out – a difficulty unlike any other on Western Australian goldfields. Bayley did find some gold but it seems he wasn’t particularly impressed with this area because he returned to Perth. From here he travelled back to Southern Cross where he once more became acquainted with William Ford.

Ford had been working in the mines for nearly a year when Bayley arrived but he was able to relate some adventures of his own to his friend that amounted to almost certain confirmation of the claims made by McPherson earlier.

Arthur Bayley

Ford, together with prospectors George Withers and Luigi Jacoletti, had found gold at a place known as Natives Grave between Southern Cross and Parkers Range to the southeast. The prospectors had sold their claim for £300 and Ford and Jacoletti had taken the job of looking after the show for the new owner. Meanwhile, George Withers had obtained horses and supplies, and travelled eastward from Southern Cross on yet another prospecting trip. Three weeks later he returned to the Cross, a spear wound in his shoulder and a chamois of gold in his pocket.

More than ever this latest event seemed to substantiate Gilles McPherson’s claims, which Bayley and Ford had discussed at some length. They decided on plans to follow up the other’s discovery but realised that in so doing, their party would need to be well founded to survive.

At this time a message arrived from McPherson for Bayley stating that he was on good gold and that Bayley should join him at Nannine, a new field on Annean Station about 500 kilometres northeast of Geraldton. Bayley made his way there as quickly as possible and together with his two mates of the time, found gold, although the results weren’t outstanding. Bayley found gold on an island in Lake Annean, later named Bayley’s Island, and it became one of the richest fields in the district.

It is not clear what Ford was doing while Bayley was at Nannine, but perhaps he and his mate were still caretaking the mine.

Throughout the history of the gold discovery at Coolgardie, Ford has always seemed to be in the background, not that he actually played any lesser part in the proceedings but rather that he was a quiet, retiring type who did not readily respond to publicity. The irony is that Ford was actually the one to discover the gold!

By the time Bayley returned and joined Ford at Southern Cross, he had managed to accumulate some £1,000 for the purchase of horses and equipment. He had also learned a little more about McPherson’s adventures and the type of country he and Ford might have to traverse on their trip. McPherson was emphatic that safe travel eastward from Southern Cross was only possible directly after rain when gnamma holes and wells would be full. Both partners were experienced enough prospectors to heed the good advice.

Bayley and Ford were fully equipped and ready to go however the rains held off, delaying their departure. A prospector named Speakman found gold at Ularring in 1891 to the northeast of town, to which they responded. Although they found a little gold, the find was not startling and in a short while the tremendous shortage of water forced them to fall back on Southern Cross.

In June 1892 rain fell in the Yilgarn District so Bayley and Ford, with 10 packhorses and eight weeks’ supply of food, set off eastwards. The country they travelled over was, and is, a heavy sandplain sparsely timbered with a short scrub gradually turning to eucalypt forest the further eastward you go. The rain ensured an abundance of feed for the horses and in the first weeks, water was fairly readily available especially in the vicinity of the numerous granite outcrops that occurred throughout the plain.

Picking up George Withers’s tracks, they followed these until they came upon a native well at the place later to be known as Coolgardie. There was a spot where Withers had dug a hole and dryblown the wash but whether this was the spot where he had obtained his gold before being speared, they couldn’t tell, though subsequent events led them to think so.

While taking his horse to drink at the native well, Ford specked a half-ounce nugget in the area later to be known as Fly Flat. That set the couple to serious specking and on that same day a total of 80 ounces was found, the largest nugget being about five ounces. This patch was about a kilometre from George Withers’s pothole. They also saw ground that had been pegged in 1888 according to a notice on it but could find no gold there themselves.

Coolgardie today

Bayley and Ford had been there about a month when a party of three white men accompanied by a black arrived and set up camp nearby. Two of these men, Jack Reidy and German Charlie, were known to Ford. The partners by this time had between them close to 300 ounces of gold and had to play it cool for the whole period the visitors remained. One can imagine the relief when the party eventually packed up and moved on. Later, where their horses had been tethered, Ford found several nuggets. Some 10 days later, having lost flour to the wet weather and about 20 pounds of bacon to the dingoes, Bayley and Ford set off to Southern Cross to replenish their supplies.

The partners wasted little time in Southern Cross and set off eastwards as soon as their provisions were ready. They joked to people that they knew, “Yes, we’ve found a little gold, and are going back to see what Jack Reidy is up to!” However, their tale was not swallowed by three young miners just out from England, and obtaining a native guide, Tommy Talbot, Baker and Dick Fosser set out to follow the pair.

The young miners had no trouble following the partners as far as Gnarlbine Rock, a large granite outcrop where there was a good soak of permanent water. While arguing the point about which track to take from the rock, Jack Reidy and his party arrived. They were able to settle the dispute and put the miners on the right trail.

Talbot and party came upon the Coolgardie rockhole and camped nearby. Next morning several horses came to the well to drink and by backtracking them, the miners found Bayley working some alluvial on the area known as Fly Flat. As a result, the flies were not the only thing to distract Bayley and although he was cordial enough to them, the newcomers were not convinced of the truth.

This occurrence is the chapter in the story of the discovery of gold at Coolgardie that has proved to be the most controversial. All those writing of it in the past seem to have been uncertain of just what did happen, and all that can be recorded with any certainty is that there was controversy at the time.

The most popular belief seems to be that after a time, the young miners, having found some gold in the vicinity of a large quartz outcrop, showed their find to Bayley and Ford. It turned out that this was the same ground the partners had previously pegged but which was not yet registered. After some argument with the newcomers, Bayley and Ford helped the trio peg ground adjacent to their own.

The upshot was it was no longer practical to keep the find under wraps. The claim needed to be registered, a reward claim made and protection sought to ensure the safety of the prospectors.

The first shaft at Bayley’s Reward gold mine

On arrival in Southern Cross, Bayley showed 554 ounces of gold to Warden Finnerty before lodging the same in the Commercial Bank, a small iron shanty with a hessian partition separating the office from the living room. In spite of his good intentions, after being lectured by Ford not to do so, Bayley went to Cameron’s Hotel for a drink. The drink loosened his mouth and he couldn’t help himself so told the story. We’ve no way of knowing whether he embellished the yarn which, after all, would well and truly have stood on its own merits, but someone among the crowd is thought to have spiked his drink putting him out of action for some time. He awakened to find his horses gone and some one hundred diggers were already on the track to Coolgardie.

Considerable good did come out of Bayley’s announcement although he would not have appreciated it at the time. For several years the country had been in a depression due to its reliance on the Mother Country and the fact that Britain itself was in a bad way financially. The Bank of England was no longer making loans, many Australian banks were failing and business generally was on the brink of collapse.

Strangely, at the time Bayley’s story broke, in spite of the high employment throughout Western Australia, Southern Cross was in the grip of a miner’s strike. Well, that was the end of the strike but the mine proprietors were no better off because practically every able-bodied man who had a wagon, horse, wheelbarrow or a good pair of legs, was on his way eastward towards Coolgardie.

It was several days before Bayley obtain a horse and then only because his old acquaintance, McPherson, turned up to sell him one. Now mounted, he set off posthaste to guide Warden Finnerty to the new find.

Meanwhile, Ford had his own problems at Coolgardie. Not only did he continually chase off the three young miners from the lease but when the first of those in the rush arrived, he had to stand guard with a gun in each hand to ensure they kept their distance – an all but impossible task for a man on his own. No doubt he was glad to see Bayley and the Warden when they finally arrived. In spite of his guard duty, Ford had not been idle. In one pothole alone he had found nuggets weighing 200, 150 and 50 ounces only three yards from the reef! Such was the richness of the find.

The outcrop was described as being 36 feet in length, six feet wide, and 12 feet in height and was not so much rock containing gold but gold holding together rock! Ford’s own words are probably worth quoting: “...and I started to break into that reef. I had a gad and hammered it in, but when ItriedtogetitoutIcouldnotasI had driven it into solid gold.”

In March 1893, Bayley and Ford sold their claim to a company for £6,000 and a sixth interest in the mine, and Bayley, having returned to Victoria, took up land near Avenel and lived, for a very short while, in prosperous circumstances. Though

an outwardly strong, athletic man, he fell into ill health, possibly on account of the privations he had suffered while a prospector, and died at Avenel, of hepatitis and haematemesis, on 29th October, 1896. He was 31 years old and left a widow but no children. His estate was valued at more than £28,000.

Ford moved to Sydney and in 1904 built a handsome sandstone Federation house called ‘Wyckliffe’ in the suburb of Chatswood. Ford and his wife had a baby girl in 1906; a son followed not long after. Ford lived quietly at ‘Wyckliffe’ until his death, in 1932, at the age of 80.

Public meeting in Bayley Street, Coolgardie, in 1894. By this time both Bayley and Ford had sold up and moved back east

The mysterious Tom Cue

By Jim Foster

Tom Cue is mostly known for his involvement in the finding of gold near Cue, the Western Australian town that bears his name. And while most people assume it was Tom who did the discovering, it was actually his partners, Michael John Fitzgerald and Edward Heffernan, who found the incredibly rich field that is now Cue. Tom was away on other business at the time the gold was found. Upon his return he was told of the find by the wildly excited pair but there was a problem. The only horse that was in good enough shape to make the trip to Nannine to register their claim was Tom’s horse, despite the fact it had just finished a hard ride. So, Tom volunteered to make the journey but strangely never put his name on the claim alongside Heffernan and Fitzgerald. Tom Cue was thought to have been born in County Cork, Ireland, somewhere between 1849 and 1855 but as no birth certificate has ever been found, it’s anyone’s guess. Counting back from the date of his death in Canada on 4th September, 1920, at the recorded age of 65, he would have been born in 1855 but the age on the death certificate was either a guess on the part of the medical examiner or a guess by his wife Eugene. The general consensus is he was born in 1850 and was 70 years old at the time of his death.

The store in Casterton, owned by Tom Cue’s parents, where Tom worked until he was 16

Tom arrived in Victoria at a very young age and travelled with his family to Casterton in south-west Victoria where his father, Thomas George Cue, set up a general store. Young Tom was given a very good education and excelled at sports. He left school to work in his father’s store but at the age of 16 decided he wanted to see the world and headed off to the Victorian goldfields. We know he worked for a short time in a saw mill near Castlemaine but after that nothing is known about him until the early 1890s, when he showed up in WA exhibiting all the signs of having done very well for himself.

The first gold at Cue was found near this small hill. It is fitting that an Aborigine is honoured atop the hill as it was an Aborigine known as ‘Governor’ who led Fitzgerald and Hefferman to the first slugs of gold found there

No one knows where Tom made his money but we can speculate. When Tom arrived in the Victorian goldfields there was still good finds of gold being made, and it is possible Tom did well on the diggings. It is also rumoured he had some involvement with the early finds of opal but there is no documentation to substantiate this. Tom often spoke with fondness of the hills and cool mountains of Gippsland but all we know is that he acquired a considerable amount of capital during those unaccounted-for years.

Arriving in WA it was noted that Tom always stayed at the best hotels in town. Rather than ride a horse with a packhorse in train, Tom travelled everywhere in a horse and trap, probably as it allowed him to carry a comprehensive range of prospecting and mining gear as well as water and other luggage. Teaming up with Michael John Fitzgerald and Edward Hefferman, the three men set out for what is now the Cue district where they made their now famous find. Tom stayed in and around Cue for a few years, becoming involved in other mining ventures and even travelling to Perth where he mixed with politicians and other shakers and movers of the era.

During this time the train tracks arrived in Cue and, perpetuating the myth that it was Tom who found the gold, the first locomotive into Cue was named the ‘Tom Cue’. During this time Tom returned home to Casterton where his father was in financial difficulties but as all the family papers have been lost, the exact purpose of Tom’s visit isn’t known though we do know his father went bankrupt. Tom’s biggest find was Cue’s Patch 10km north of Lawlers. He had found an immensely rich alluvial patch and reef that others had missed at what was to become Agnew. Naming the mine The Woronga, Tom only stayed for 18 months before selling the mine for a very large sum. The mine must have been a good one as the Ogilvie line of reef was still being worked up until a few years ago. And then once again, Tom simply dropped off the face of the Earth. There were stories that he travelled to the Cloncurry and Chillagoe districts and in the latter was involved in the establishment of the copper mining industry, but again this is only speculation. It is also rumoured that he was at Broken Hill at one time. The next chapter in Tom Cue’s life was a prospecting trip up the Amazon River which he helped finance and organise. And while we know this expedition took place and that Cue was heavily involved, nothing is known about what the expedition uncovered. After the Amazon trip Tom returned to Victoria and met Eugene Spencer Tyson, nee Wills.

Tom and Eugene travelled to Vancouver, Canada, where they were married and had a daughter they named Eva. Eva never married and died in 1972. The family then travelled to Alaska as by now Tom was an avid mining speculator who journeyed far and wide in search of investment opportunities. At one stage he was known to be in Circle City (just outside the Arctic Circle) but whether for investment purposes or to “take the waters” at the hot springs there is unknown. When he took his family to Dawson City he would have taken the famed White Horse Pass rail line from Skagway to Lake Bennet, then boarded a stern-wheeler below Miles Canyon for the last leg down the fabled Yukon River to Dawson. But, like much of Tom’s life, why he went to Dawson City and what he did there is a mystery. In 1900 Tom and his family were reported as living in Vancouver before returning to Australia in 1902 on the SS Africa, via Cape Town, South Africa. Not long after, Tom returned to Cape Town by himself, giving his age as 51.

In 1903 he was living in Toorak, Melbourne, and gave his occupation as mining engineer and his age as 55. It’s little wonder there is so much speculation as to the exact date of his birth when Tom himself seemed to have no idea of how old he was.

As befitting a man so shrouded in mystery, there are no known photographs of Tom Cue. In 1991 a couple were fossicking for gold near Cue and found a metal printer’s plate depicting Tom Cue filling his pipe. And that is all we have to identify a man described as being nearly six feet tall and quite burly

From shipping company records we know that Tom and his family travelled extensively, often taking trips to the United States, Canada, England and back to Australia. What he and his family did when they arrived at those destinations we will never know. Much of this travel might have involved mining and investment but we don’t know for sure. Tom must have invested wisely in many mining companies to have accumulated the kind of wealth that allowed him to travel so extensively. Even in the early days of the great Western Australian gold rushes, there is little evidence that Tom did much actual mining himself. He certainly did some prospecting as evidenced by his big find at what it now Agnew, but there is no reference to him actually getting his hands dirty. Tom, it seems, was willing to invest in others and to share their success when it came.

Tom Cue’s death certificate shows that he died from inflammation of the inner lining of the heart and hardening of the arteries. He lived his last days in Vancouver a long way from the heat and dust of the Australian goldfields. His wife, Eugene, and daughter, Eva, moved back to Australia after his death

Some people might think less of a man who lets others get down and dirty then claims a share of their hard work, but in the mining game, and especially prospecting, there would have been far fewer miners and prospectors who could have afforded to get out there and make a go of it if it wasn’t for men like Tom Cue. And any speculator or investor takes a huge risk when grubstaking a prospector or miner. Many was the investor who never saw a penny in return after their original investment disappeared into the hungry earth.

Eugene Cue, the wife of Tom Cue, was originally married to Peter Tyson before divorcing him for drunkenness

To further deepen the mystery surrounding Tom Cue, it would appear there has never been a gold lease or a claim with the name Tom Cue, or Thomas George Cue, or simply T. Cue recorded anywhere in Australia. Not even the Woroonga mine which he sold.

Ballarat’s golden “Canadian” connection

By Kevin Ruddick

Visitors to Ballarat will readily notice two 1850s goldrush terms in constant modern commercial use, namely, “Sovereign” and “Eureka”. You can get anything from a Eureka Pizza to pre-cast products from Sovereign Concrete. But another goldrush term, “Canadian”, also gets a pretty good workout, and with regards to gold production, “Canadian” was far more important than either Eureka or Sovereign. This article was originally going to be about an interesting mining relic I found while detecting in the Canadian Forest, on Ballarat’s eastern fringe, however the origins and golden history of all things “Canadian” at Ballarat are so fascinating they deserve some explanation.

The 4-gram bit specked by the author in Canadian Forest

There are five usages of the word Canadian at Ballarat and, in historical and geographical order, they are: Canadian Gully, Canadian Deep Lead, Canadian Creek, the suburb of Canadian, and Canadian Forest. All have gold, but certainly not in equal proportions. Canadian Gully was first opened at its shallow head in September 1851, probably by the notable David Ham, but more seriously in mid1852. It was named after a Canadian digger called Swift, who prospected there with compatriot Canadians and Americans. But what is the relationship between Canadian Gully and the other “Canadians”? Remembering the adage that a picture is worth a thousand words, I have drawn a flat plan and a vertical cross section through the Canadian Gully (Ballarat East) to clearly explain what a thousand words would struggle to do.

Chunky bits panned in Canadian Creek

Harrie Wood’s authoritative Notes on the Ballarat Goldfield informs us that by February 1853, the miners, sinking down to rock bottom (or pipeclay) in the Canadian Gully, started tracing their way down the gully, finding that they had to go to ever greater depths to find rock bottom and the gold. But what fabulous gold awaited them! In the short space of 11 days in January 1853, not one, but three monster nuggets, the likes of which the world had never seen, were found in quick succession. The largest, named the “Sarah Sands”, was at that time the heaviest nugget anyone in the world had ever laid eyes on. The three monsters weighed 1,619 ounces; 1,117 ounces; and 1,011 ounces, the last two being found in the same claim! All the other claims in the gully averaged 420 ounces. As the gully reached the flat below, the golden rock bottom was now so deep it started being referred to as the Canadian Deep Lead. It took a sharp 90-degree turn to the left (north) and the claims were now paying an unbelievable £2,000 per man.

But the best was yet to come. When the Canadian Lead amalgamated with the Prince Regent Lead, a small claim on this site called the Blacksmith’s Hole produced an incredible one ton of gold. Remember, this was a small-area claim worked by a windlass and eight men, with only limited short drives. I suspect it was possibly the richest small claim worked by a windlass in the history of the world. I would be interested to hear of any rivals. No wonder the name “Canadian” became famous throughout Europe. And a little further north, where the Canadian Lead entered Dalton’s Flat, another monster nugget of 1,177 ounces, called “The Lady Hotham Nugget”, was found. This nugget and the three monsters already mentioned, would soon be eclipsed by the “Welcome” and the “Welcome Stranger” nuggets. The Sarah Sands nugget remains the fourth largest ever found in Australia, a delirious dream for the four relative new chums who took it back home to England with them on the good ship Sarah Sands, the inspiration for its name. Today, if you’re looking for the historical location of Canadian Gully, you’ll find it behind the fence of the Sovereign Hill Park, at the Park’s southernmost end, where their horses graze and the light show is held. It is parallel, and near to, Elsworth Street and while you won’t be doing any metal detecting there, you can still pan specks in Canadian Creek.

The pulley in its pre-restoration state

The creek, at the surface, roughly follows the same course as the Canadian Lead, buried deep below it. I have found many pennyweights there (but not ounces I’m afraid) and some chunky bits too. Thirty or more years ago, my son Chris and his mate, Terry, were poking around in Canadian Creek looking for old bottles rather than gold. Terry looked down and specked a 1.5-ounce nugget right beside the York Street bridge, in the middle of Ballarat suburbia! He still has it. But it’s getting hard to find specks there now and you feel a bit odd panning behind someone’s backyard fence.

The pulley after sand-blasting and painting

The Canadian Forest is another story however, and people certainly detect there. It is so named because it adjoins the suburb of Canadian, but on the other side of the suburb, and nearly 2km from Canadian Gully. There is still plenty of evidence of mining there, with many shallow shafts near the Pax Hill scout camp. A storage dam and head race hint at past ground sluicing, which is also clearly evident. But this was never a big producer like Golden Point or Canadian Gully, and old newspaper references to gold mining in the Canadian Forest are rare. The word is that detectors are finding a few subgram bits there on occasions – very rare occasions I suspect. Then again…one day I was walking my dog on the dirt track just a few metres short of the forest. It had rained that morning, exceptionally heavy rain, the heaviest in my memory, and I was shocked to see that every pebble and grain of sand had been washed clearn away, leaving a smooth, clay road, bereft of any covering. The thought of gold immediately crossed my mind and I kept my eyes peeled as there were several little mine heaps only metres away, right on the road reserve. Lo and behold, a 4-gram nugget was sitting in the clay gutter, completely free of any sand or stones. The rain had washed absolutely everything away, but the nugget, being heavy, just sat there, and was perhaps exposed for the first time ever. I had walked past that little nugget every night for years but it took a freak storm to reveal it. For some inexplicable reason, I get a bigger thrill specking gold than any other way of finding it.

The author’s flat plan of Canadian Gully

Vertical cross-section of Canadian Gully drawn by the author

I did say this article was originally going to be about a mining relic I’d found, so I’d better get on with it. A few months back I was trying my luck with the detector in the Canadian Forest about 100 metres from where I’d specked the 4-gram bit. I was working around the aforementioned old shallow shafts and heaps when suddenly Above: The pulley in its pre-restoration state Above, right: The pulley after sand-blasting and painting Below: The author’s flat plan of Canadian Gully Bottom: Vertical cross-section of Canadian Gully drawn by the author Australian Gold Gem & Treasure 9 my detector nearly blew its head off. Just under the leaf litter I dug up an old pulley block. It was quite rusty, but the word “Digger” was clearly legible, being cast into the pulley. I can’t be certain, but being in the middle of a goldfield, it’s reasonable to assume that miners used it to help haul up their bucket or kibble.

I took it home to clean it up but it was so rusty it gave the impression that with a little rough treatment, it might fall apart. I took a risk, got it professionally sandblasted and it was surprisingly sound with the detail around the axle now clearly visible. I then primed and spray painted it black. Just for a bit of fun I built a tripod over some old diggings to let the grandkids have a play around with it. I’m sure the miners would have built something much more substantial – probably involving a windlass. Some research on the internet to investigate the “Digger” brand name revealed that a company called Gray’s Pty Ltd from Victoria manufactured picks, shovels, hoes and so on under the brand name “Digger”, but that was all I could ascertain. Maybe someone else can add to the story. My brother-in-law has a great collection of heritage Aussie tools and artifacts in his own backyard patio museum, so my old pulley block has a home to go to where I hope it will be appreciated by many.

Footnote: The Canadian Forest has recently been made into a park by the Victorian government. It is now called Woowookarung Regional Park, in deference to the local Wadawurrung people. Interestingly, detecting is allowed and the remnants of mining have not been destroyed. At 640 hectares, it is one of Ballarat’s best kept secrets. There might still be some gold on offer but the trees, birds, animals and beautiful wildflowers are the real treasures of Ballarat’s Canadian Forest

Did Dan Kelly and Steve Hart survive the Glenrowan Inn fire?

by Trevor Percival

History tells us that an enterprising woman named Ann Jones established the Glenrowan Inn in 1878 to service travellers, but that it only ran for two years before it was the scene of the last stand the Kelly Gang. By the time the siege was over, with Ned Kelly captured and the rest of the gang dead, the inn had been destroyed by fire, lit by police to flush out gang members. Dan Kelly’s and Steve Hart’s charred bodies were returned to Kelly family members in the evening of the siege, on Monday 28th June, 1880. The body of Joe Byrne, who was killed earlier in the siege by a police bullet, was retrieved unburnt from the inn. Ann Jones’s 13-year-old son, John, and the hostage, Martin Cherry, later died from wounds suffered in the shootout. There were in fact more than 60 hostages in the Glenrowan Inn when the first shots were fired. Ned Kelly was tried, convicted and sentenced to death. He was hung at Old Melbourne Gaol on 11th November, 1880, aged 25. His “reported” last words were “Such is life”. This is what history tells us. But what if some of that history is wrong. What if Dan Kelly and Steve Hart didn’t perish in the Glenrowan Inn fire? One year, while fossicking on Chinaman Creek, I met an elderly gentleman who said he had met Steve Hart’s sister who claimed Dan Kelly had moved north to live in a hut outside of Mitchell in western Queensland. The gentleman, in his travels, had also met Steve Hart who had shown him burn scars on his back and said that he and Dan had hidden in the cellar and escaped during the night. A Queensland Sunday Mail article by Wayne Kelly (no relation to Ned and Dan) which published on 17th July, 1988, said that one person who scoffed at the stories of Dan Kelly’s and Steve Hart’s escape was Frank Rolleston of Eton near Mackay. Rolleston said that because of the rumours of an escape, for years afterwards, any old greybeard camped in isolation was not only suspected of being Dan Kelly but a published series about a man who said he was Dan Kelly had brought protests from at least five other “Dan Kellys” living in various corners of Australia.

But the article also suggested that Dan and Steve, after learning of Ned’s capture and therefore his certain death by hanging, went by ship to Argentina and then to South Africa. Long-time Kelly researcher, Kieran Magill, of Redbank Plains, told the Queensland Sunday Mail that it was indeed possible Dan and Steve had escaped. Mr Magill, who had studied official records of the Kelly Gang, including those of the Royal Commission which followed, said an escape could have been made in the final hours of the Glenrowan siege.

Glenrowan Inn

Amateur historian, Hilda Hornberg, of Redland Bay, also told of a meeting she had had in Roma in 1933 with Dan Kelly, then in his seventies. Ms Hornberg said Dan was on his way to a station to see Steve Hart and the man calling himself Dan Kelly had shown her and others his burn scars. Another person, J. Hunter, of Ipswich, contacted the Sunday Mail saying his sister, who had been a trainee nurse at Royal Brisbane Hospital, had told of a dying patient with burn scars who said he was Dan Kelly. The man would have been in his eighties. No-one disputes the fact that the remains of two very burnt bodies were later retrieved from the smouldering ruins of the inn and it was simply assumed they were the charred corpses of Dan Kelly and Steve Hart. Their identification however, was solely based on the word of Matthew Gibney, a priest from Western Australia, who was on a trip to the colonies on the east coast of Australia and was travelling by train between Benalla and Albury when he heard about the siege while the train was stopped at Glenrowan. Gibney decided to go and take a look. Gibney had never set eyes on Kelly or Hart but later, when he heroically entered the burning Glenrowan Inn in an attempt to rescue anyone inside, he said he had discovered the then unburnt bodies of Dan Kelly and Hart, who he surmised had committed suicide.

Dan Kelly - Bushranger

But the bodies were never positively identified by the police and the Kelly family, who took charge of the blackened remains, refused to give them up for an inquest. In a second Sunday Mail article, this one by Ken Blanch, which published on 26th November, 1989, it was revealed that a man by the name of William Bede Melville, in August 1902, had cabled several Australian newspapers from Capetown in South Africa, that two men had identified themselves to him as Kelly and Hart. Melville, an ex-Sydney pressman, was at one time private secretary to Sir George Dibbs, three times Premier of NSW. Melville said the two Australians were brought to his hotel room in Pretoria one night in Africa at midnight by a mutual acquaintance. What follows is part of Melville’s account of the discussion that took place: “A bottle was opened, pipes were filled and long after midnight, Dan Kelly combed his tangled hair with his fingers and said, ‘Steve here, and me, and Joe Byrne was in that pub all right. Ned got away nicely, and we was to follow him, but Joe Byrne was boozed and we couldn’t pull him together. When we wasn’t watching, he slipped outside and was shot. After that, two drunken coves was shot through the winder. They wanted to have a go at the traps, so we give them rifles, revolvers, powder and shot. The firing where they dropped was too hot for us to reach them, so our rifles and revolvers were found by their remains. This was why they thought we were dead. I’m sorry for those coves as they didn’t take my tip and go out with a flag, but they’d the drink and the devil in them. Well, Steve and me then planned an escape. We was in a trap and we had to get out of it. The next thing was how to leave the pub.

Joe Byrne - Bushranger

We had spare troopers’ uniforms with caps that we always carried so we put them on. There were some trees and logs at the back so we hung along the ground for a few yards and then blazed away at the pub just like the troopers and you couldn’t tell us from the bloomin’ traps. We retreated from tree to tree and bush to bush, pretending to take cover. Soon, we was amongst the scattered traps and we banged away at the bloomin’ shanty more than any of them. The traps came from a hundred miles around and only some of them knowed each other. They didn’t know us anyhow. They couldn’t tell us from themselves. We worked back into the timber and got away. Soon afterwards, we saw the old house nearly burnt to the ground and we thanked our stars we was not burnt alive. Well, we got to a friend’s (shepherd’s) hut and we stayed three days and the shepherd brought us papers with whole pages about our terrible end, and burnt up bodies and all that sort of stuff. We read of Ned’s capture and we was for taking to the bush again, but the shepherd made us promise to leave Australia quietly. He gave us clothes and money. We got to Sydney and shipped to Argentina. We had a good time of it and didn’t get interfered with and we didn’t interfere with anybody also. We pretty much kept to ourselves so as not to bring attention to us. A few years ago we crossed to South Africa where the Boer War broke out, and being out of work, we went to the front. We had some narrer escapes but nothing like the Glenrowan pub. We’re off in an hour or so but we don’t want the world to know. You can say what I tell you, but wait three weeks or a month. Listen, if you give us away, this little thing in my hand, a friend of mine, will blow you out.’ And he put the point of the revolver into my eye. I looked at him sharply, and the awful glare in his eyes and the suspicion that convulsed his face, convinced me he meant it. The other day, six weeks later, I was surprised to encounter Dan Kelly and Steve Hart in Adderley Street, Capetown. ‘Well,’ said Kelly, ‘You kept your promise. We have not been interfered with. You may write what you like after termorrow.’ I did not enquire about their destination and they did not volunteer the information.”

Ned Kelly at Old Melbourne Gaol

Some more of the details in Melville’s account appeared years later in a story that published on 18th December, 2007, in the Brisbane Courier Mail. The article was accompanied by a photograph of Mr Collin Sippel of Murgon. Mr Sippel and Bill Roberts, a former Mayor of Murgon, were investigating the deathbed confession of a gentleman, Bill Meade, who had died in the nearby Wondai Hospital in 1938. Meade went to his grave claiming he was actually Steve Hart of the Kelly Gang. Mr Sipple was six-years-old when he first met Meade who taught him leatherwork when he was living in the Redgate area near Murgon. Mr Roberts had also known Meade in his younger days. There was talk of raising money to have the body of Meade exhumed for modern DNA testing. Mr Sipple and Mr Roberts said the Bill Meade they remembered was similar in stature, appearance and age to early photographs of Hart. In September of 2009 I rang Mr Sipple to enquire how the investigation was progressing and was told that they were having problems in raising enough money or getting a sponsor to invest in the process of finding out if Bill Meade’s statement that he was Steve Hart, was true or false. Nothing ever came of the matter and Bill Meade’s bones lie undisturbed in his grave. Bill Meade was 78 or 79 when he died in 1938 so he would have been born around 1860 making him either 20 or 21 at the time of the Glenrowan fire. Steve Hart was born on 13th February, 1859. He was 21 when he “died” at the siege of the Glenrowan Inn.

So, did Dan Kelly and Steve Hart make it out of the burning Glenrowan Inn all the way to Argentina and then to South Africa to fight in the Boer War, before returning to Australia decades later? The truth might never be known but it makes a good story all the same.

Head across to the Apple Isle for some gold and gems

By Jim Foster

In the three times we have visited Tasmania, and having spent almost six months in total in the Apple Isle, we had never done any prospecting simply because we didn’t think there would be much, if any, reward for our efforts. It just goes to show how wrong you can be. In fact, gold can be found in many places in Tasmania. We didn’t know it at the time but when we visited Corinna on the Pieman River on the west coast, we were very close to the Whyte River goldfield. We even climbed over a huge moss-covered quartz blow out on the Whyte River walking track that could have shed gold. We did visit a couple of gold towns but these were built to service deep mines and we weren’t aware of any alluvial workings in those places. The fact we didn’t have our detectors made it a moot point, but when we return to the Apple Isle next year we won’t be making the same mistake. Gold is thought to have first been discovered by a convict at Nine Mile Springs near Lefroy, in north-eastern Tasmania, in 1840.

Then, it is said, John Gardner found gold-bearing quartz in 1847 on Blythe Creek, near Beaconsfield. Officially however, the first payable alluvial deposits were reported in the north-east of the state in 1852 by James Grant at the Nook, also known as Mangana, and Tower Hill Creek. And the first registered gold strike (2lb 10oz) was made by Charles Gould at Tullochgoram in the east, near Fingal, south of St. Marys.

A very beautiful ounce-plus nugget from the Lefroy area of Tasmania

Alluvial and reef gold was then found in the many creeks running into the Pieman River near Waratah, and into the Whyte and Hazelwood Rivers on the west coast. Having been to the Pieman and Whyte, I can attest to how rough and wild the terrain is and I have no desire to brave the leech- and mosquito-infested wilderness of the Whyte or Pieman goldfields to do a little prospecting, despite the fact there is still good gold to be found there. Everything I have read and heard about Tasmanian gold these days is that it is mostly sub-gram stuff. While that might be true in many areas, there are still nuggets being found down there that tip the scales at more than an ounce. We actually don’t mind what size it is – gold is gold and as we only prospect for fun these days, we get as much satisfaction and pleasure out of a pretty one grammer as we do out of a 1-ouncer. As a bloke once said to me “Anyone can find the big lumps but it takes real skill to find the flyspecks.”

Tasmania has designated fossicking areas for both gold and gemstones. No license is required to work these areas

Looking at maps of the Tasmanian goldfields we see that they range from the east coast to the west and are concentrated in the north. The biggest blank space is down in the south-west but that’s because most of that incredible wilderness has never been explored let alone prospected. At Specimen Hill, Nine Mile Springs (now Lefroy) in the north-east, the first alluvial gold was discovered by Samuel Richards in 1869.

As can been seen from this map of just the north-east corner of Tasmania, there are plenty of goldfields but you do need a license and permission for most of them

Reef gold was actually identified at this location in 1867 with production mainly restricted to the Native Youth, Chum, Volunteer and New Pinafore Reef mines.

An SDC2300 is probably the best detector for Tasmania. The small coil is ideal for tight undergrowth and the detector’s ability to find tiny scraps of gold means you’re more likely to find at least some of the right stuff

News of Richards’s discovery precipitated the first big rush to Nine Mile Springs and a township quickly developed beside the present main road from Bell Bay to Bridport. Dozens of miners pegged out claims there and at nearby Back Creek, and the usual goods and services providers followed in their wake.

A specimen from the Apple Isle

While the Specimen Hill find was alluvial gold, most of the gold in the Nine Mile Springs area was bonded to quartz below the surface. Consequently, companies moved in to crush the ore and the Lefroy Goldfield became the first profitable goldfield in the colony.

Osmiridium nuggets aren’t worth as much as gold but at around $560 an ounce, they’re not chicken feed either

The largest gold nugget ever found in Tasmania weighed more than 243 ounces and was found in 1883 by J. McGinty, D. Neil, and T. Richards at Rocky River in the north-west near the township of Golden Ridge. It should be noted that more gold was obtained from the surrounding area than the famous Golden Ridge itself. Overall nearly 30,000 ounces of gold was won from this location. If you want to do some detecting in Tasmania my advice is to join the Prospectors and Miners Association of Tasmania (PMAT). They have members who know Tasmania very well and they can put you onto the best proclaimed fossicking areas around the state. They also have a forum which will enable you to garner a great deal of useful information. But if gemstones are more to your liking, you’ll be pleased to know that Tasmania is literally awash with them. One of the most popular and easy-to-get-to spots if it’s sapphires you want, is at Weldborough in the north-east on the Weld River. While you’re there the Weldborough Hotel is well worth a visit and there is a camping ground right beside the Weld River.

A handful of Weld River sapphires. Most Tasmanian sapphires have been found in the creeks and rivers that drain the Blue Tier and Mt Paris area in the north-east of the state

Osmiridium is another metal that is popular with prospectors in Tasmania at the moment. It is a natural alloy of the elements osmium and iridium, with traces of other platinum-group metals, and at the time of writing was fetching about US$400 an ounce. The main use for osmiridium was as hard, durable tips for fountain pen nibs however the popularity of ballpoint pens led to a huge reduction in the market for fountain pens and hence for osmiridium, although the alloy has some other uses. You can readily research osmiridium on the internet and while it might not be worth as much as gold, it’s still an interesting metal to find. Goldfields in Tasmania are generally much smaller than in Victoria or Western Australia and most are on private land or leases, or both.

If you go gold prospecting or gemstone fossicking on Tasmania’s west coast without the right gear and a whole lot of experience, at least leave a note for the coroner

Local knowledge is a must if you want to access goldfields that are not proclaimed fossicking areas. Prospecting opportunities in Tasmania also depend on the type of country you’re in. Much of the northern area of the state compares favourably with parts of Victoria but the west coast goldfields such as the Tarkine, Whyte River and Pieman goldfields are in dense temperate rainforests where even the locals get lost. But if you’re prepared to brave the wild west, make sure you’re carrying whatever it takes to ward off the marauding armies of leeches, sand flies and mosquitoes. If you’re interested in prospecting for gold or gemstones in Tasmania you’ll find a great deal of information online as well as on the Tasmanian Detecting club’s forum. Simply visiting Tasmania as a tourist is extremely rewarding but throw in some prospecting or fossicking, like Cheryl and I plan on doing next year, and your visit will be even more memorable.

In search of Thunderbolt’s treasure

BY TONY MATTHEWS

When Frederick Wordsworth Ward, alias the notorious bushranger Captain Thunderbolt, died from a gunshot wound on 25th May, 1870, he left behind an enduring mystery. Where did he hide the £20,000 in gold and notes he was reported to have stolen during his seven years of bushranging? Some historians claim that Thunderbolt spent all his ill-gotten gains, or that he never actually stole that amount. Others claim the man who was shot and killed on that fateful May day wasn’t Thunderbolt, and that the real bushranger lived a happy, and presumably wealthy life, in the Roma region of Queensland.

Myth and mystery interwoven with fact and fantasy, but the legend of Thunderbolt’s fabulous treasure still inspires those who are prepared to believe it has remained hidden in the rugged country of northern New South Wales for the past 150 years. Frederick Ward was convicted in 1856 of horse stealing and sentenced to 10 years hard labour on Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbour. He served out four years before being conditionally released but was again arrested while on ‘ticket-of-leave’ for horse stealing and breaking his parole. Returned to Cockatoo Island to complete his original sentence and serve an additional three years, Ward served only two years before making a desperate hid for freedom. One cold September night in 1863, Ward and another convict named Frederick Britten broke free of their shackles and plunged into the harbour, ignoring the danger of sharks which were attracted to the area by waste products from several nearby slaughterhouses. Both men managed to struggle ashore to the mainland exhausted but free. It was to be the beginning of an era. Ward was just 27 years old, a wanted criminal on the run with a price of £25 on his head, and so he turned to the only profession left open to him. He became a bushranger.

Captain Thunderbolt on the day of his wedding to Mary Ann Bugg

Ward was a superb horseman and expert in bushcraft. For the next seven years he roamed the New England region of New South Wales, holding up travellers, inns, coaches and prospectors. The name “Captain Thunderbolt” came about after Ward robbed the tollbar house at Campbell’s Hill near Maitland on 21st December, 1863. It was Ward who started calling himself that though the Thunderbolt legend has it that when the customs officer was rudely awoken by Thunderbolt banging loudly on his door, he is purported to have said, “By God, I thought it must have been a thunderbolt.” Another account has the customs officer asking, “Who’s that making such a thundering noise?” And Ward answering “I’m a thunderbolt. The noise you hear is the thunder and,” pointing his revolver at the customs officer, “this is the bolt!” Ward was joined in his nefarious activities by a motley collection of wouldbe bushrangers however none could match him for cold cunning and horsemanship. His one constant companion was a welleducated Aboriginal half-caste girl, Mary Ann Bugg, whose aboriginal name was Yellilong. Living a harsh and rugged life in the bush, dogged by danger and constantly hunted by the police, she stayed with her lover until she finally died of pneumonia, having born Thunderbolt three children. According to legend, it was Yellilong who taught the bushranger his signature song: “Her Bright Smile Haunts Me Still.”

This photograph of Captain Thunderbolt clearly shows the bullet wound above the left breast and the stitched incision caused by the post mortem examination

After her death, Thunderbolt became quite sullen, and is reported as saying that he wished it was all over. “My life’s a misery,” he told one of his friends, “I wish I’d been shot long ago.” Thunderbolt finally got his wish. It was a cold day in May, 1870, when he bailed up his last victim, a hawker named Giovanni Capasotti near Blanche’s Inn at

Church Gully, six kilometres from Uralla. After the robbery, the bushranger went to the inn and Capasotti made all haste to Uralla and informed the police. Upon arrival at Blanche’s Inn, Constable Mulhall fired his pistol in the direction of Ward who was at the time testing an inferior horse, but the trooper’s horse took fright and Ward rode off. However an off-duty trooper, Constable Alexander Binney Walker, who was mounted on a well-bred and fast horse, finally cornered Ward at Kentucky Creek near Uralla. Walker called upon Ward to surrender, the bushranger refused and after a brief gunfight in which Ward’s horse was shot out from underneath him, Ward was hit at close range, the bullet entering his chest and rupturing both his lungs. The fight continued for a few seconds longer but Walker’s gun was empty and so he used the butt to smash Thunderbolt’s face into a bloody pulp. The whole exchange had taken just a couple of minutes but when it was over, Thunderbolt was dead and the secret of where his treasure was hidden died with him.

Wood engraving of the moment Captain Thunderbolt was shot by Constable Walker

Twenty years after Thunderbolt’s death, a young lad hunting for birds’ eggs stumbled upon a cave in the remote Goulburn River region. Inside the boy discovered a bottle containing a thick wad of mouldy £5 notes and it was assumed this was a small portion of Thunderbolt’s haul. But what of the remainder? Many people in the New England area still claim it’s there somewhere, just waiting for some lucky bushwalker to find it. Ward was 5 ft 8¼ ins (173cm) tall, slight, and of sallow complexion with hazelgrey eyes and light-brown curly hair. He undoubtedly had great nerve, endurance and unusual self-reliance and his success as a bushranger can be largely attributed to his horsemanship and splendid mounts; to popular sympathy inspired by his agreeable appearance and conversation; and to his gentlemanly behaviour and avoidance of violence; he also showed prudence in not robbing armed coaches, or towns where a policeman was stationed. The last of the professional bushrangers in New South Wales, Ward’s seven years of bushranging was the longest of any of Australia’s highwaymen. Some historians have equated this with success, but if dying a violent death at just 35 years of age can be called successful, it’s little wonder no-one followed in his footsteps.

The gunfight at Cooksvale Creek

When Fred Lowry died he reportedly said “Tell ‘em I died game,” which might not be as apocryphal as Ned Kelly’s supposed last utterance “Such is life”, but what is a fact is that Lowry never mentioned the hiding place of the thousands of pounds taken from the Mudgee mail robbery on 13th July, 1863, the theft of which made his name as a bushranger. Thomas Frederick Lowry was born in Homebush (then Liberty Plains), Sydney, in 1836 and grew up in the Young district of NSW. He and his mate, John Foley, stole horses and served time at Bathurst gaol. In company with Ben Hall and other members of the gang, he had robbed Barnes’s store at Cootamundra, then moved on to robbing mail coaches. He held up the Goulburn mail coach at a place called Big Hill, assaulting a man called Richard Morphy during the exploit. However it was the Mudgee mail which really made his name, the incident taking place 16 miles from Bowenfields. Inside the coach were a Mrs Smith of Ben Bullen who had about £200 on her person and Henry Kater, an official of the Mudgee branch of the Australian Joint Stock Bank. He had stowed a bag containing £5,700 of old bank notes (withdrawn from circulation and on their way to Sydney to be destroyed) in the boot of the coach.