Life and death in the Queensland gold escort

With the discovery of gold in Australia in the 1850s, there came a time when the police force had to perform extra duties in and around the gold mining towns. As well as making arrests, and serving warrants and summons, one of their main responsibilities was gold escort duties. The first ever gold escort departed Mount

Alexander near Castlemaine, Victoria, on 5th March, 1852, carrying 5,199 ounces of gold and arrived in Adelaide two weeks later. Eventually, 18 trips were made between 1852 and 1853 transporting 328,502 ounces of gold. The Victorian- goldfields to Adelaide route was notable for the distance and amount of gold carried – almost a quarter of all gold, 1,520,578 ounces, transported within Victoria during the gold rush years from 1851 to 1865.

Queensland separated from NSW in 1859 and between 1861 and 1867 there were a number of gold discoveries at Clermont, Cloncurry, Cape River, Nanango, Gympie and Kilkivan. Because of the vast distances that had to be travelled in order to deliver the gold to the banks, and because Queensland could no longer draw on police manpower from NSW, the gold escort was formed in Queensland in 1864.

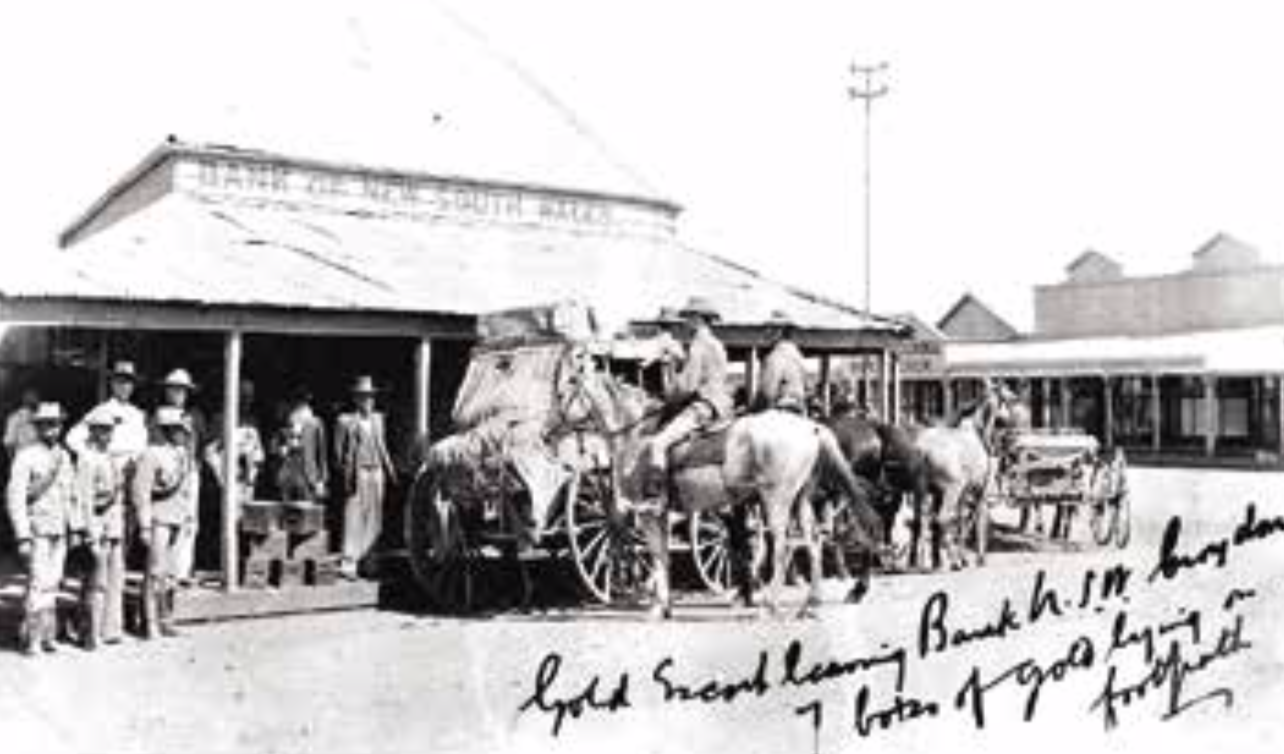

Gold escort group photographed at Normanton, c.1895

Because of the dangers involved, the pay was doubled for any policeman while he was actually escorting the gold to its destination. The ever-present danger of robbery, accidents, and attacks from Aborigines were part and parcel of life for the escort police.

At the time of the first gold discoveries, the aborigines in some of the gold-producing areas were extremely troublesome and in the years before the police took charge of the gold escorts, there were numerous attacks with some prospectors and troopers losing their lives.

When the first goldfields opened up, most of the terrain encountered was difficult to traverse and packhorses were used rather than wheeled conveyances. Each horse carried up to 1,200 ounces of gold and was led by one constable. In front were two men with fully loaded guns at the ready, followed at the rear by another armed constable. Also, a number of native troopers were usually employed to lead the extra packhorses which carried blankets, cooking utensils, tents and so on as the trip usually took many days.

As the escort police and horses were not employed solely for gold escort work, this operation took too many police away from the district and in one instance, when 16,000 ounces was conveyed from Georgetown to Croydon, it left one station closed and five other smaller stations with only one or two men on duty. The trip took 22 days and involved an enormous escort squad of 15 police, eight native troopers and 65 horses.

The gold escort about to depart Georgetown, c.1900

Another worry for the Commissioner was the need to procure and keep horses. Each horse had to be kept in top condition for such duties and a lot of them simply couldn’t last the distance. In times of drought, when hay and corn was more expensive, it had to be brought in from larger towns and the cost to the Government was considerable.

In 1870 it was announced by the Commissioner that gold escort vans would be built. This would not only reduce the number of police needed to escort the gold, but would also decrease the number of horses needed, even though four horses were used to pull the coach which could carry up to one ton.

Following is an extract from the 1876 Police Manual that outlines the rules by which gold was to be escorted between the goldfields and the banks.

1 – On the regular lines of road, or on other lines where the amount of gold or treasure is large, the escort will be composed of one officer, one sergeant, and four constables.

2 – One mounted constable will form the advance guard, riding from 100 to 150 yards in front of the conveyance, according to the nature of the country through which the treasure is in transit. One mounted constable will march on the right, and another on the left flank, keeping as nearly as possible parallel with the conveyance, and at such a distance from it, not exceeding 100 yards, as the nature of the country will permit. The other constable will follow in rear, at about the same distance behind the conveyance as the one in front is before, all keeping constantly in view of the officer in charge.

3 – The sergeant will march immediately behind the conveyance, except when ordered by the officer to see that the men are performing their duty properly, under which circumstances the officer will take the sergeant’s place, so that at all times during the march, either the officer or the sergeant may be immediately behind the conveyance.

Gold escort waiting to load seven boxes of bullion at Croydon, c.1905

Depending on the cargo carried (gold, coins or notes) the escort fees varied. Sometimes escort fees would rise if it was a particularly dangerous journey and more men were required, or if a ‘Special Consignment’ was carried. In 1894 the miners on the Georgetown goldfield, angered by the amount of money the Government was skimming off the top, asked for the fee to be reduced from sixpence to fourpence per ounce. In one instance the Government received £184 in fees for the carriage of gold from Georgetown to Croyden but only incurred an actual cost to them of £30.

The Government were raking it in as there were monthly escorts on the Gympie- Maryborough run, the Gilbert and Cape

River goldfields to Townsville run, and the run from Clermont to Rockhampton. But the danger of robbery by bushrangers or attack by aborigines was always present and by 1889 the cost of maintaining the gold escort service had become such a serious issue that it was decided public coaches could do the job just as well.

Cobb & Co. coaches were used with the minimum number of men employed to guard the gold. Inspectors were also removed from gold escort duties. Later, consignments of gold and valuables were carried by train as the railways opened up. Usually only one constable was used in conjunction with railway employees to escort pay boxes to the mines and to escort gold and valuables out.

MURDERS OF POWER AND CAHILL

Seated L to R: Sergeant Julian, Constable Cahill, Constable Power and Gold Commissioner Griffin. The two Native Mounted Police (rear) are not named. (Supplied by Queensland Police Museum)

In November, 1867, troopers John Francis Power, 25, and Patrick William Cahill, 27, were given the responsibility of escorting £4,000 in cash and bullion from Rockhampton to Clermont on horseback.

Rockhampton’s Gold Commissioner at the time, 35-year-old Thomas John Griffin, offered to join the escort on the pretext of the troopers’ inexperience but it was later discovered his real plan was to ride as far as the Mackenzie River, stage a bushranger robbery and steal the cash and bullion for himself.

Griffin owed £252 to six Chinese diggers who had entrusted him with their gold for safekeeping. Griffin subsequently gambled this away. The Chinese men made repeated demands for the return of their gold or its value but Griffin was unable to pay the debt, became increasingly desperate and probably around this time, in August 1867, came up with the idea of robbing the gold escort.

The day before the murders, on November 5, 1867, the three men arrived at the Mackenzie River crossing and set up camp close to where the Bedford Weir sits today. Throughout the day, the trio reportedly frequented a nearby bush pub and Griffin took the opportunity to drug the drinks of the two police officers.

Later that night, Griffin reportedly shot the two men dead and rode back to Rockhampton, burying the money and gold along the way. After Griffin had arrived back in Rockhampton, news broke that Cahill and Power had been discovered dead near where they had camped on the Mackenzie River near Bedford’s hotel, and the money that they had been escorting to Clermont was missing.

A party, including Griffin, was assembled to travel to the scene to investigate the deaths which were initially believed to have been a result of poisoning, after the discovery of two dead pigs near the scene. However, after a post-mortem examination by Dr David Salmond, it was discovered the two troopers had both been shot in the head. No evidence of poison was found, but Dr Salmond expressed an initial view that the two men had been affected by a narcotic of some type and were shot while in a “state of stupor” from its affects.

Griffin was arrested at the scene at approximately 10am on 11th November, 1867, following the exhumation of the two bodies. It was alleged Griffin did “feloniously, wilfully, and with malice aforethought, kill and murder Patrick Cahill and John Power.” His trial started on 16th March, 1868. On 24th March the jury disagreed with Griffin’s plea of “not guilty” and the judge sentenced him to be hanged at the Rockhampton Gaol on 1st June, 1868.

In a bizarre turn of events, more than a week after he was buried, Griffin’s grave was dug up and his head was cut off and stolen.

Rockhampton journalist and historian, J. T. S. Bird, claimed that the main culprit was local Rockhampton doctor, William Callaghan, who took the head away and buried it in a friend’s garden before collecting it. Bird claimed the skull was in the doctor’s local surgery until his death in 1912. There have since been unsubstantiated reports that the skull now sits on a shelf an upper class private residence in Rockhampton.