December 2025 Issue Available At All Leading Newsagents!

Read the featured article from this month’s issue below

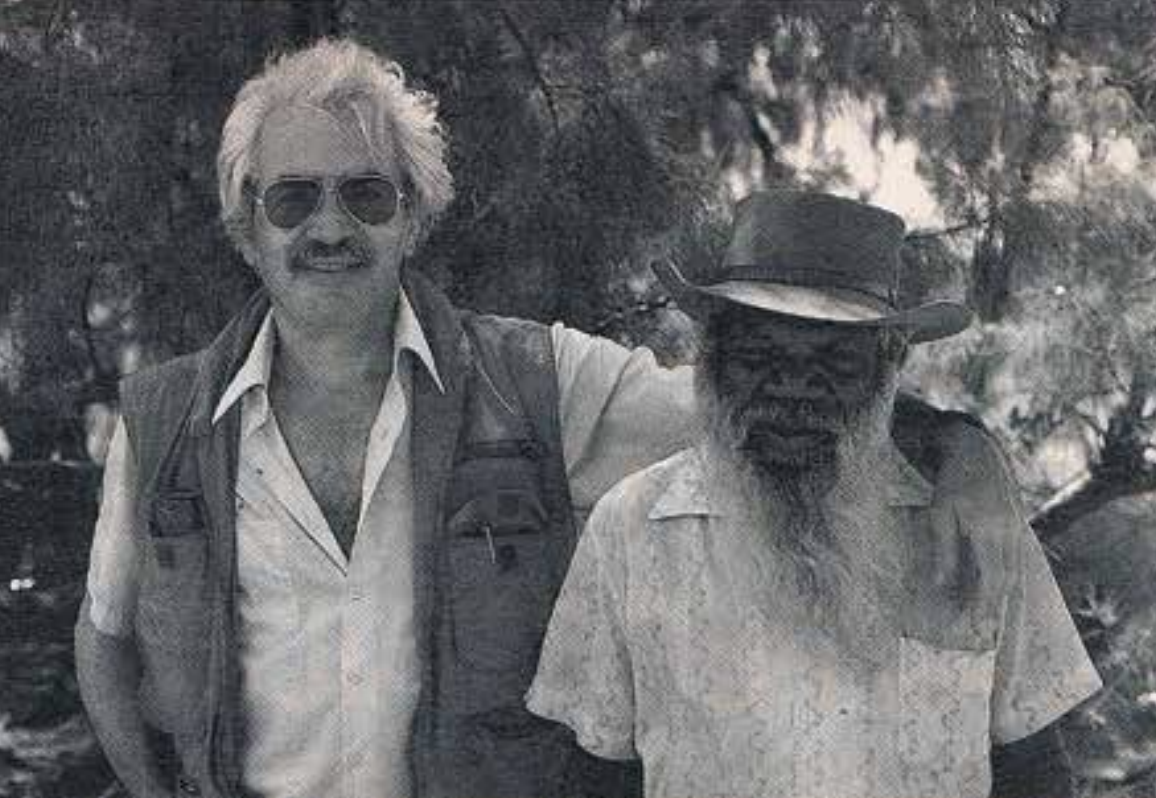

Some goldfields snakes have teeth

By BSM

This is a sad but true story which I was personally involved in some years ago. Only the names of the people involved have been changed to protect the guilty, which is the custom in Australia due to our defamation laws which, more often than not, protect the guilty rather than provide some degree of justice for innocent victims. Cutting to the chase, following is an account of the greed and dishonesty that sometimes takes hold when a lot of gold is involved. The main characters in this saga were John and Brad, who, while working in partnership, discovered a leader which turned out to be quite rich. I first met John many years ago in outback Western Australia. I came across him quite by chance as I was driving into an area that looked good on the geological map. I stopped for a yarn and finished up camping with him for several weeks. He turned out to be one of the most knowledgeable people on prospecting and bushcraft I have ever come across. He also had hundreds of stories he could recount about events and people of the west, from politicians and police officers right through to ordinary prospectors like himself. He had been personally involved with a number of these people over the years, and some of them were well-known identities. As with most old-school bushmen and prospectors, he was able to get around the goldfields just by memory, instinct and a simple map of the area. He had no use for new-fangled gadgets such as a GPS. And now to Brad. I had met him on several occasions over the years and while I found him to be a competent young prospector and a decent, honest person, he was a little too inclined to be trusting of people he didn’t know well.

A couple of years after my first encounter with John, I ran into him again in the supermarket of a small outback town in Western Australia. Upon seeing me he rushed up and told me that he and Brad had found a rich leader on unpegged ground and he needed a hand to work it. He asked if I’d be interested in helping for a share in the proceeds. I answered that as long as Brad was amenable to having an extra partner, I’d be happy to help. “Let’s ask him and see what he thinks about it,” I said. John said that Brad wasn’t in town with him, that he was back looking after the camp, but that he was sure it would be all right. “I’ll draw you a mud map and meet you out there when you’ve done your shopping,” John smiled. Later in the day, with my shopping done and my water drums filled, I drove out to Brad and John’s camp and on arrival discovered that John was absent. To say that Brad was surprised to see me would be an understatement. It was obvious John had made no mention to Brad of the proposition he’d put to me. Leaving Brad to it, I wandered off and set up camp some distance away. A couple of hours later John drove back into camp and came over to say hello but made no mention of his earlier offer and neither did I. The next day I had a look at the hole Brad was digging. As he broke up the ground he threw chunks up onto the side. John then checked them with his detector to get the larger lumps of gold which he put into one of several large white glue drums. The rest of the ore was sorted for quality and put into various 44-gallon drums sitting on a large tandem trailer parked alongside the excavation.

At the end of each day, John put the glue drums containing the larger coarse specimens and nuggets into his caravan for safe keeping. Brad had none of the gold in his possession. Each day Brad would work in the hole and John would go out detecting, returning in the afternoon to sort through the material that had come out of the hole. Brad explained that whatever John found while out detecting went into their kitty but that he had only picked up a few grams in the last couple of weeks. I went out prospecting each day and managed to find enough gold to keep the wolf from the door. On my fourth day out, I came across a large patch containing several hundred open detector holes and when I looked up the slope, I saw John’s vehicle parked by some trees. I then spotted him detecting nearby and quickly moved away from the area without attracting his attention, concluding that neither Brad nor John wanted me to know about this part of the operation. After a week or so the drums on the trailer were full and Brad and John towed it away to have it processed by Renae, who had the equipment to carry out this part of the operation on his lease about 120 kilometres away. On their return, Brad suggested that they dolly some of the specimens so that he could go down to Kalgoorlie and sell the gold because he was getting a bit short of cash. Brad had funded the entire operation with no financial input from John. After some discussion, John grudgingly agreed.

The next day Brad and John dollied up the contents of two of the large glue drums. That night, after I’d finished dinner, I strolled up to the campfire where we usually sat and talked for an hour or so but neither Brad nor John was there. I saw John’s caravan light was on and his door was open, so I wandered over. John was inside running the contents of the two dollied drums through a very fine sieve and putting the gold into another container. He looked a little startled when he saw me but recovered quickly and explained that Brad had a headache and had gone to bed early. He then got all of the other drums out of their hiding places in his van and showed me some of the larger pieces. By my reckoning there were at least 800 ounces in the pieces I saw! The next morning, I heard John’s car drive off just after dawn and a little while later, as I was leaving camp, I noticed Brad had a cut-off drum full of water and was starting to pan off some fines. I stopped by and asked him how it was going and why John wasn’t at the pan off. Brad said John had gone detecting because it didn’t need the two of them to do the panning off. I then asked Brad if he was getting much in the pan and he said there was very little and that most of it was extremely fine and would need mercury to separate it. At this point I told him about the amount of gold hidden in John’s caravan and about the episode with the very fine sieve, and that I felt he might getting stitched up.

That evening I heard raised voices up at their camp but decided against intruding. They could settle their differences without my help. Before dawn next morning I heard a vehicle start up and drive away after daylight and noticed that John’s car and caravan were gone. I had my breakfast and wandered up to Brad’s van. Brad then told what had occurred when John had returned to camp the day before. “When John arrived he asked me how much gold I’d got from panning and I told him just over a hundred grams. I said that the rest was too fine to separate and I’d tipped it back into the drum to process later. John then accused me of being a thief and said there had been a lot more gold in it than that. When I told him that you’d seen him fine sieving the dollied material before I got it to pan off and that you’d also seen the drums of gold specimens in his caravan, he said you were a liar. He then picked up the drum of fines and went into his van. Early this morning his car suddenly started up and drove off before I could do anything about it. The battery in my car is flat so I couldn’t go after him.” The equation went something like this: Brad had paid for all of the fuel, the hire of a generator and kanga hammers, had done all of the work in the hole, was unaware of the large patch that John was working, and had finished up with 100 grams (he was lucky John didn’t take that as well). When Brad eventually got to Renae’s lease, he was told that the ten 44s of ore that had looked so rich had, after processing, only returned a little over an ounce in total but because he felt sorry for Brad, Renae said he wouldn’t charge him for the processing and generously gave him 15 grams of gold. How’s that for kindness? It’s pretty obvious that John and Renae, a couple of creatures so low they could hide under a cockroach’s arsehole, had stitched up Brad from the outset. They say what goes around comes around but whether John and Renae were looking the other way when karma eventually hit them, I can only hope.

Harvey’s Nugget

By Mike Osborn

In the pages of Australia’s history, tales of fortune and misfortune abound, with the former a source of nourishment for the “gold fever” in all of us. Luckily though, even the worst of our misfortunes seem to fade with time. As precious a thing as gold most certainly is, it can be a cruel addiction, bringing out the worst in human nature between even the closest of friends. The story of “Harvey’s Nugget” is a tale of cruelty indeed, one that I won’t forget easily and one that shows that “gold fever” is as real an affliction as any disease can be. Harvey’s position in life is an envious one. As a staff writer for the American National Geographic magazine, he travels the world to far flung and exotic locations, wielding an expense account that provides him with a comfortable existence, free of the budgetary constraints that might restrict the average traveller to a limited time frame and an overloaded credit card. Determination, hard work, months at a time away from a growing family and an ability worthy of his post, had earned him that position. “Coin shooting” as he calls it, is Harvey’s one and only selfindulging passion, a pastime relegated to the limited free time he has to himself in his home town of Washington DC. Combing the parks, bus stops, playing fields and public areas of a major capital city with a metal detector may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but for Harvey, it satisfied his prospecting instincts and kept him in touch with his ambition of one day sifting through the goldfields of Australia, looking for the “fist-sized nuggets” he had heard, read, thought and dreamt about. His trusty Fisher Gold Bug detector was antiquated and somewhat battered by the time he came to realise his dream.

The saga of “Harvey’s Nugget” had an innocent enough beginning. The editors at the National Geographic offices in Washington had decided to feature Western Australia’s northwest in an issue of the magazine. The process of selecting writers and photographers had come and gone with Harvey accepting the writer’s assignment with a delight that must have bemused his superiors. For Harvey, it was the start of an adventure that would fulfil a decades-long ambition – prospecting for gold in the Australian goldfields. He had packed his trusty Gold Bug and a pile of research material and boarded the plane for the long flight to Darwin (before travelling to the starting point of his journey at Kununurra in WA’s Kimberley). I had never met Harvey before and I was to be his guide and companion for the two months that were allocated to him to travel the north-west and put together the information required for the feature.

National Geographic feature writer, Harvey Arden

My credentials didn’t include a successful career as a gold prospector but I knew enough to try and dampen some of Harvey’s expectations of abundant and easily-detected nuggets in the Kimberley, Pilbara, Gascoyne and Murchison regions of WA. I had spent a year or so at Kalgoorlie, the heart of WA gold-bearing country, and while I had dabbled with detecting, the greatest reward for my efforts was the well-rusted workings of an old leveraction carbine! Harvey also categorised his prospecting expertise below that of a rank amateur so luck was going to have to play a major role if any trace of gold was to cross our paths! It was at Old Halls Creek in the Kimberley where Harvey and I made our first foray into a “goldfield”. It was very much a touristoriented approach, purchasing a “prospector’s licence” to work a patch set aside by the leaseholder to accommodate the wanderings of would-be fortune seekers on his ground. We were assured that gold was to be found if we worked hard and long enough! As luck would have it, I found a rusted lever from a carbine to match the one I’d found at Kalgoorlie but that was all that came to light and we moved on. Changing from our allocated patch proved to be a poor decision. “Trespassers will be shot” read the hand-painted sign at the entrance to the next track. We assumed it wasn’t a joke and decided to try our luck further south in the more expansive fields of the Murchison.

Meekatharra was to be the setting for our next prospecting escapade. Harvey was determined to stay on the less troublesome side of the law as it applied to detector-wielding gold seekers such as us. For one thing, the signs that dotted the pock-marked landscape gave us ample warning of the consequences of poking about on a lease without the appropriate invitation. The second and perhaps more important consideration was that if Harvey was to write about our escapades in any detail, he would need to show that he had kept within the constraints of the law. This meant finding a “friendly” prospector; someone who would be willing to share his precious lease with a couple of “out of towners” for a day or two. The responses my approach received were interesting to say the least and needless to say, none were positive.

I tried a different tack and sought advice from the local Department of Mines. The staff were friendly and extremely helpful but of course there were no available leases up for grabs, at least not anywhere within coo-ee of anything resembling gold country. It seems that companies had blanketed just about any area of worth, and a few extra just for good measure. The last resort was an approach to one of the large company operations.

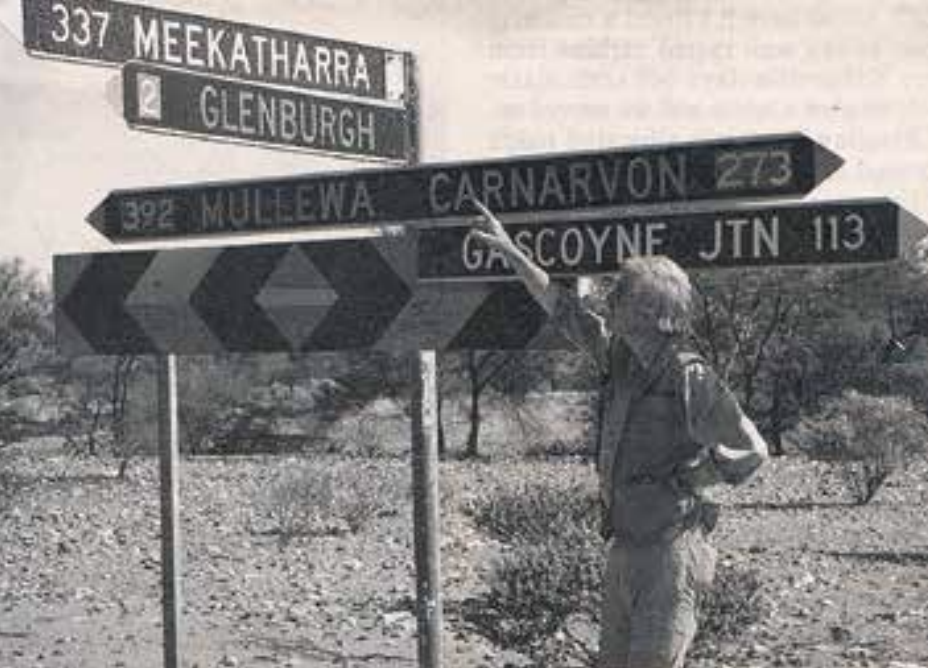

Harvey Arden looking for directions to his nugget

My introductory call to one of the largest privately owned mines was received politely, with understanding and best of all, with an invitation to visit the mine office to discuss the matter. I have no doubt Harvey’s connection with National Geographic drew the invitation. We were treated to coffee and a tour of the crushing plant and workings. I was impressed – Haulpak mining trucks, semi-trailers, 4WDs and machinery were everywhere. This was indeed a big operation. It was hard to imagine that it was all owned by one man. I had broached the subject of detecting on the mine lease earlier that day during the introductory phone call, and didn’t strike any opposition. “Would you mind?” I asked again, just to make sure. It seems that we were the first to ever ask to do such a thing and were told tales of those who hadn’t had the courtesy to do so, even some of the mine staff, it seems, couldn’t resist the temptation of working the ground after hours. Permission was granted and we were pointed in the direction of the main mine site several kilometres away with instructions to contact the foreman of the site. As we exited the airconditioned offices, the lady who had been so helpful and accommodating when I had first contacted the company, said: “Of course, if you find anything over an ounce you will have to let us know!” Harvey and I took it as a joke and to this day I’m sure it was meant as one.

Excitement and anticipation were literally oozing from Harvey by this stage. The mine foreman was a little surprised that we had been given approval but was friendly and accommodating. He took us to a small hillock almost totally surrounded by a dry salt lake, and this was to be our allocated patch. Before the foreman left, he gave us a little history of the hillock, saying that this precise location was the site of many of the largest and most prolific nuggets that the lease had produced. I passed on the “if you find anything over an ounce” joke and he laughed. The shine from my rising interest in possibly finding a speck of gold was sullied with his parting comment “The ground has been worked real hard; give it a go though, you might get lucky.” I don’t know why but I had naively thought that we would end up in some little out of the way spot, instead we were within one hundred metres of Haulpaks dumping overburden onto a mound that was heading in our direction. Harvey was too excited to worry about much and was already slipping the earphones into place. After 20 minutes or so of probing the ground, Harvey walked over to our parked Landcruiser muttering something about changing the batteries in his detector. A few minutes later and with a newly-charged machine, he was back at it, swinging to and fro, occasionally chipping with his rock pick at nothing more significant than the pull-tops of beer cans or chips of metal from the bulldozer tracks.

We were no further than 20 metres from our vehicle when Harvey walked over to me and queried “What do you think this is Mike?” The tremble in his voice belied his expectations. We both knew that it was gold! A nugget the size of an egg! Dirty and dusty maybe but it was gold. Just a few minutes earlier I was thinking to myself that perhaps Harvey’s trusty Fisher was about as useful as an ashtray on a motorbike but at that moment, I worshipped it as a marvel of microchips and plastic! The remainder of the afternoon flashed past and nightfall saw us back at the comfortable lodgings of a Meekatharra motel. There we were, two grown men acting like hyperactive kids at a birthday party. That one piece of gold triggered a euphoria in Harvey that was contagious. The smile could barely fit across his face. The nugget was caressed, fondled, washed in the bathroom sink, examined with a magnifier, names were thought up for it and the circumstances of its discovery were recounted a dozen times over. Neither of us had any idea of the weight or value of the nugget. It contained a small amount of rose-coloured quartz but in essence it was all gold. At dinner that night in the motel dining room, the temptation to weigh it became too much to bear. We must have looked a strange sight to the chef and kitchen staff as Harvey gently released the lump of rock onto the scales alongside the rack of spices. One hundred grams! Back in the motel room we began to return to an acceptable level of behaviour for adults and the significance of Harvey’s find began to set in.

Harvey finally realized his ambition to go gold prospecting in the goldfields of Australia

The implication of those words “of course if you find anything over an ounce you will have to let us know” began to play on Harvey’s mind. I helped him wrestle with his conscience for an hour or so. Should we tell the mine staff? What will be their reaction? Worst of all, will they want to take possession of the nugget? To be truthful, the thought of keeping the gold overrode Harvey’s honesty for a short while. The fact that we had been treated more than fairly by the mine management, the usefulness of the nugget for Harvey’s article and simply being able to tell the tale of the nugget to friends without the nagging feeling that a touch of dishonesty can bring, saw us arrive at the same conclusion. First thing the next morning I would phone the company to announce the discovery of yet another memorable nugget from that small hillock. We discussed the pros and cons of this course of action late into the night and finally slept, comfortable in the thought that at least we were doing the “right” thing. Harvey’s fears of having to hand over the nugget were allayed as I hung up the phone. “Great,” said the girl from the mine office. “Bring it in and I’ll get it cleaned in acid for you. We have a box or two around here to put it in if you want.” But the next day in the mine office, the atmosphere was no longer one of smiles all round. The girl who had been so friendly the day before, walked out of the plush office and returned a short time later, bringing with her a geologist. You could have sliced the air with a knife. I was feeling uncomfortable to say the least and the expression on the face of our now, not so friendly, acquaintance was as good an antidote as could be found anywhere for the gold fever that had gripped Harvey and me for the last 18 hours.

It seems that “Harvey’s Nugget” had created a dilemma for the mine administration and an embarrassment for the geologist. Clearly the administration was in damage control mode and we discovered why after poring over maps and pinpointing the location of Harvey’s find. To me, a 100-gram nugget was the find of a lifetime. Even if it wasn’t me that picked it up, just to be a part of it was a thrill. To an operation such as the show we were at, I daresay the value of that nugget at the time would not exceed the tea break costs for one day. I was struggling to understand the problem that confronted the nervous and embarrassed duo standing in front of me. The nugget rested on a table between us, (us and them that is), with ownership open for debate. Awkwardly, the story unfolded. To start with, no one at all considered it likely that Harvey would realise anything other than dusty shoes and drained detector batteries in our allotted patch. The geologist was somewhat red-faced as the mound of overburden and tailings heading in the direction of “Harvey’s Hillock” (we took the liberty of renaming the site) was due to cover it in a day or so. Obviously, the operational plans for that area would need closer scrutiny. Finally, the main stumbling block between the nugget and Harvey’s possession of it was the owner of the mine. As it turned out, the owner was overseas at the time of our visit and although our friendly and accommodating girl had sufficient authority to offer us permission to do what we had done, a decision on the final resting place of “Harvey’s Nugget” would need to be made by the mine proprietor. A polite verbal and mental tug of war over the temporary custody of the nugget took place between our girl and Harvey, resulting in promises of its safe keeping until the mine owner could be contacted. An assurance was given that under no circumstances would the nugget be crushed. It was planned for a studio photograph of the nugget to be taken for the magazine article.

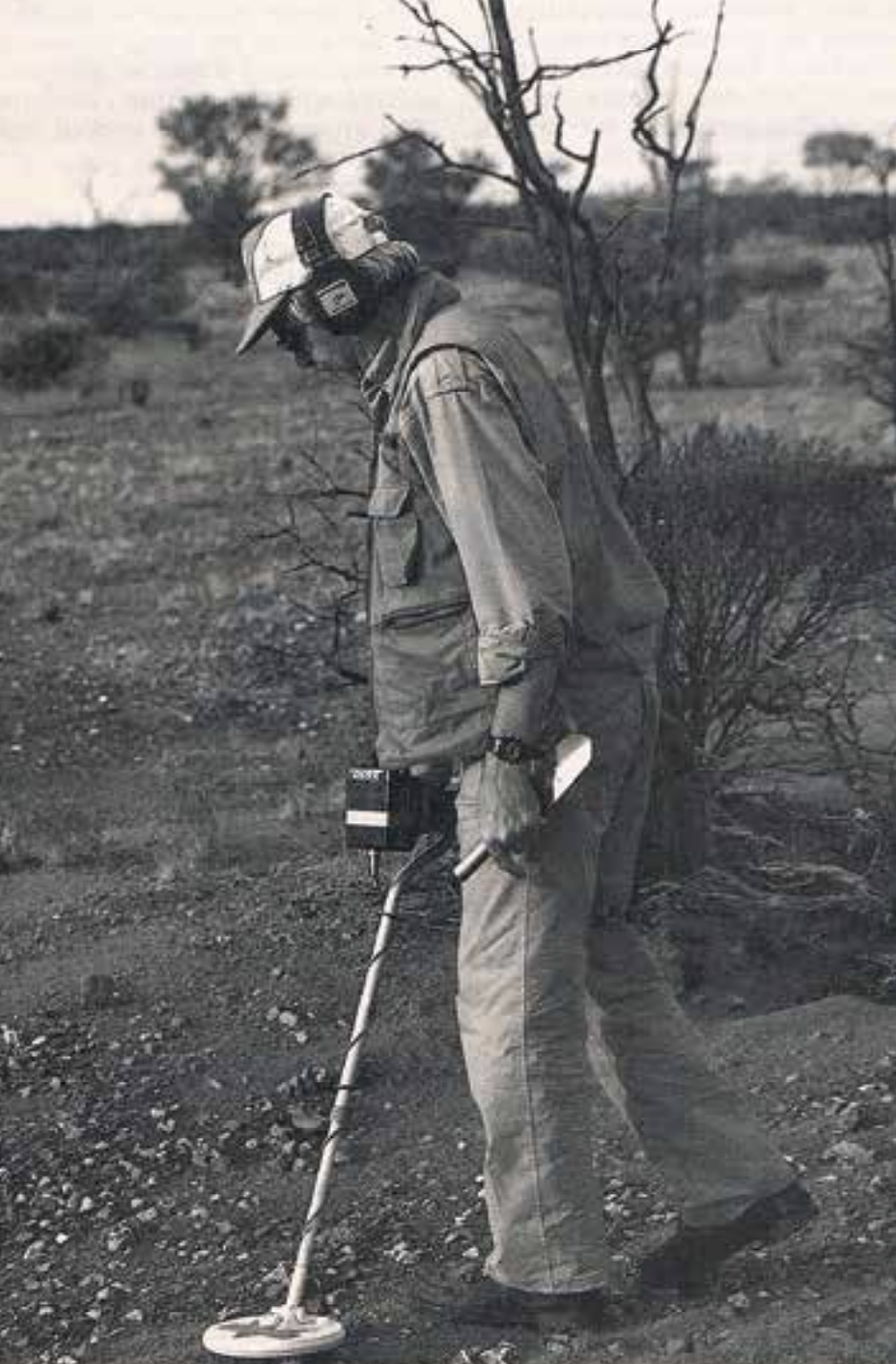

Enlisting the help of one of the locals near Halls Creek in the Kimberley, where specking nuggets after the monsoon rains of the “wet” season can be done with a degree of success

A letter was penned to the owner explaining the situation exactly as it had occurred, apologising for the inconvenience and as a sincere gesture, Harvey offered to pay for the value of the nugget because for him, the nugget was the fulfilment of a lifelong ambition and he wasn’t about to let it get away. We left Meekatharra that day secure in the knowledge that even if all else failed, the proposed photograph would enable fond memories of that fulfilled ambition to be had. The following weeks saw us attending to the various other aspects of our task. My persistent telephone calls to the mine raised little response, with the offered explanations of “he is still overseas” doing little to bolster my assurances to Harvey that we Australians were a fair and just race. I mulled the situation over in my mind time and again and thought that even if the worst came to the worst, Harvey would still possess his nugget, albeit after having to part with the cash if need be. My last phone call to Meekatharra was from Darwin on the day of Harvey’s departure from Australia. “The nugget doesn’t exist anymore. We put it through the crusher,” was the cold and curt response. I walked into Harvey’s room not really knowing what to say. I had wanted for him to leave Australia with an impression of our country and its population that would be reflected in his article. Harvey obviously sensed my uneasiness before I spoke. I blurted out the news that signalled the demise of his dream. His reply reflected an attitude that mirrored his approach to life’s cruel blows: “Ah well, the real value of that nugget is in my heart and they can’t crush that.” We wandered down to the bar and toasted the end of the nugget with a beer. The brand? Swan Gold!

Editor’s Note: Harvey Arden worked as a senior writer for National Geographic magazine for 23 years and produced some of the magazine’s most memorable stories. He was also the editor, author and co-author of numerous books. He passed away on the 17th of November, 2018, at the age of 83.

The Zuytdorp mystery

By J. Heather

For months I’d been dreaming about “Welcome Strangers” and “Golden Eagles”, scanning geo maps and fossicking out every scrap of info about the old Western Australian gold town of Cue and its surrounding districts. But after two rain-filled weeks, freezing winds, hot rocks and a collection of spent bullets, I’d thrown in the towel and retreated to the Murchison Club Hotel to console myself with a whisky or two. In conversation I told a local my luck was out and I’d soon he heading home. He nodded sympathetically and suggested “Before you shoot through, nip out to Walga Rock.” I thought he might be putting me onto gold, but he smiled and said, “No gold mate but there’s a ship out there, or at least a painting of a sailing ship. They reckon it’s been there for about 300 years.” In lieu of gold nuggets I was interested. I hadn’t run across anything about sailing ships in my researches so I decided to spend my last day checking this one out. Just past Austin Downs station I caught sight of the rock, a great monolith, rising out of the sandplain, glowing orange-red in the morning sunshine. Once there it didn’t take long to find the painting. Situated at the end of a gallery of Aboriginal rock paintings, it’s a very simple work rendered in a white material, possibly bird lime. There’s no mistaking what it’s meant to represent and it looks very old. Underneath the ship there are several lines of what appears to be writing of some sort but I wasn’t able to make any sense of it. Gazing at the painting I felt certain that the artist must have been a European, so completely different is it to the surrounding works of art. But there were no Europeans in these parts 300 years ago. Or were there? Back in the city I found out what I could about the strange painting and discovered that it had been tentatively dated at between 200 and 300 years old by the WA Museum. The writing was described as an attempt by an illiterate person to form letters and there the matter rested.

In June 1712, with 280 seamen and soldiers on board, a Dutch East Indiaman, the Zuytdorp was wrecked on the WA coast near Shark Bay, about 60 kilometres north of the present-day town of Kalbarri. The ship was driven onto rugged limestone cliffs which in parts reach a height of more than 250 metres. It’s a dangerous and inhospitable stretch of the coastline and it wasn’t until 1927 that the remains of the wooden ship were discovered by Tom Pepper, who was fencing and trapping dingoes. It was definitively identified as the Zuytdorp by geologist Phillip Playford in 1954, based on coins found at the site. It soon became apparent that many people had survived the disaster. There was evidence they had managed to salvage gear from the ship including nautical instruments, casks, barrels and sea chests. They had hauled these things to the cliff tops, established a camp there and constructed a huge signal fire. They were aware that a fleet of four East Indiamen had been due to leave the Cape 17 days behind them and they must have pinned their hopes on being picked up by these ships.

Amongst the ashes of the signal fire, globules of molten brass and the hinges and other metal parts of chests were found. This leads one to picture the terrible situation the survivors found themselves in. Perhaps in the distance a lookout caught sight of the white sails of one or more ships of the flotilla and shouted for the fire to be lit. As those same sails began to vanish over the horizon everything that would burn was desperately thrown onto the blaze in a last-ditch effort to attract attention. One can imagine the despair as they watched their chance of rescue slipping away. Walga Rock is a long way from the Zuytdorp wreck site, about 350 kilometres in fact, but both are at the same latitude and are linked by the Murchison River which flows into the sea at Kalbarri. The survivors would have had to move south to encounter it and there is evidence that they did move to the south-east to obtain water from a native soak that was still in existence after white settlement of the area. Before this they may have lingered for a time near the wreck site, hoping perhaps that a search vessel might be despatched after their failure to reach Batavia (no such ship was sent). But as summer arrived, they would have been driven from the waterless environs of the cliffs and their search for both water and food would almost certainly have brought them into contact with the aborigines. It’s not hard to imagine the castaways throwing in their lot with these people.

The sailing ship at Walga Rock

The Murchison is a seasonal river and is a natural highway into the interior. All along its course there are soaks and rockpools where game come to drink. Walga Rock is on the Sanford River, a tributary of the Murchison. Its size and the extensive rock paintings there identify it as a focal point in aboriginal culture and religion and a natural gathering place. Perhaps, nearing the end of his lifespan, a lonely Dutchman chose this important site to record his memories and under this painting attempted to leave a message in the manner of his own civilization. Inland nothing has ever been found to definitely link the Zuytdorp with the unexplained ship painting but there remains time yet. When she struck the cliffs the Zuytdorp was carrying a rich cargo including more than 248,000 guilders in cash, consisting of ducatons and half ducatons, schellingen and various pieces-of-eight. Scores of these coins have been recovered from the cliff tops indicating that they were carried there rather than flung up by the ocean. Later, in making contact with the aborigines, these coins may have been used as gifts or trade tokens and some actually made their way into the interior, carried either by the aborigines or by the survivors themselves. There were also reports of some aborigines with European features. Searching for such relics from the Zuytdorp would be like looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack, but keep it in mind on your next gold-hunting trip to the Murchison fields.

Platinum - the dethroned king of metals

It wasn’t until 1557, after the Spanish conquest of South America, that the first published references to a hard-to-melt metal, platinum, were noted by Italian scholar and poet, Julius Caesar Scaliger. Specimens of the metal were not received in Europe until the middle of the 18th century. The fact is, platinum had been worked by man, primarily for decorative purposes, for many thousands of years, particularly by the ancient Egyptians and the Incas. They just didn’t have quite as much of it as they had gold. Actually, all the platinum ever mined would only produce a cube 17 feet on each side, less than 5,000 cubic feet. Even with today’s modern placer mining methods, it takes up to 10 tons of ore to produce one ounce of platinum. Well-formed crystals of platinum are very rare and the common habit of platinum is nuggets and grains. Pure platinum is unknown in nature as it usually alloyed with other metals such as iron, gold, nickel, iridium, palladium, rhodium, ruthenium and osmium. These last five metals are collectively known as the Platinum Group and one of them, palladium, is traded as a commodity just like gold, silver and platinum.

Until 10 years ago, platinum reigned supreme as the world’s most expensive precious metal, but as the world recovered from the last big financial crisis, surprisingly, platinum not only lost its crown to gold, but at one point slipped behind palladium and the other Platinum Group Metals. However, in the minds of the general population, platinum is still top of the heap. A “Platinum Credit Card” is regarded as having a higher status than a Gold Card. A Platinum Record is one up on a Gold Record and Platinum Class is more expensive than Gold Class. Platinum is 20 times rarer than gold and 20% rarer than palladium. It is one of the densest metals being 11% denser than gold and almost twice as dense as silver. Its melting point is almost double that of silver too. Gold’s value is closely related to its safe-haven status in times of political and economic turmoil whereas platinum’s value is more aligned with its technological and scientific applications. At the time of writing, gold was fetching AUD$5,182.10 per ounce, whereas platinum was only fetching AUD$2,087.85 per ounce. Both are Troy ounces of which there are 12 to a pound.

A 701-gram nugget of platinum from Russia

The presence of other metals tends to lower the density of platinum from a pure metal specific gravity of 21.5 to as low as 14 and very rarely higher than 19 in natural specimens. The heaviest known substance is osmium, which has a specific gravity of 22.5, compared with gold which has an SG of 19.3. During the first 40 years of the 20th century, platinum was the preferred metal for wedding and engagement rings and was almost always used to enhance the beauty of diamonds and other gemstones. Just before World War II, platinum was declared a strategic material and its use in most non-military applications, including jewellery, was prohibited. During this time, white gold was developed as a replacement. Many people refer to platinum as “white gold” but they are incorrect. White gold is in fact an alloy of gold with white metals such as nickel, silver and palladium. For example, 18-carat yellow gold is made by mixing 75 per cent gold with 25 per cent of other metals such as copper and zinc. But 18-carat white gold is made from mixing 75 per cent gold with 25 per cent of nickel, silver or palladium. The amount of gold is the same but the alloy is different. And when white gold rings are new, they are coated with another white Platinum Group metal, rhodium, which is very white and hard but it does wear away eventually.

Notable occurrences of platinum include the Transvaal in South Africa; the Ural Mountains, Russia; Columbia; and Alaska, USA. Australia does have platinum, although it’s not a major producer on a global scale. While historically significant platinum deposits were found in Fifield, New South Wales, and alluvial deposits in Victoria, platinum is typically a byproduct of other mining operations, particularly nickel and copper. However, recent discoveries and exploration efforts are raising the profile of platinum in Australia.

From riches to rags

By Barbara Peck

He was a popular man of his time and at one stage was even a Member of Parliament. Frank Stubley had it all, including a very generous nature, and that was his biggest problem. He couldn’t help himself. If he saw an old mate down on his luck, Frank would reach into his pocket and give all. Some were genuinely needy but a lot were flyby-nighters and Frank couldn’t distinguish between the two. But if the truth be known, he probably didn’t care. He had enough for everyone. Years later it would emerge who his true friends were but by then it was too late for Frank Stubley. In the heady days of the gold rush era of Charters Towers in Queensland in the 1870s, Frank Stubley was employed as a blacksmith at the “One And All” mill but dreamed of gold and riches as much as the next man. One day there was talk at the mill about a new reef called the “St Patrick’s” being full of potential but the syndicate of 20 miners who owned the mine were stopped just when they were in sight of the rich gold vein. The Queensland National Bank, which was financing the syndicate, cut off their cash advance because the limit of the loan had been reached. Frank had been waiting for his chance to get into a “good thing” and from his wage as a blacksmith had managed to save enough to immediately purchase 17 of the 20 shares in the St Patrick’s. In no time the St Patrick’s Block Mine was earning him £1,000 a week and another mine he invested in, the “Brian O’Lynne”, was also showing good returns.

Mosman Street, Charters Towers, c.1880

UNPROFITABLE VENTURES

But no sooner had Frank pocketed the cash than he let it slip through his fingers. Friends and strangers alike were always taking liberties with his kindness and happy-go-lucky nature. His cash flow was also at odds with some disastrously unprofitable ventures into horse gambling and a number of other wild speculations. But Frank lived for the day and could afford to because his mines were extremely profitable. He was so popular that from 1873 to 1878, he served as the Member of the Legislative Assembly for the seat of Kennedy. He also became the first patron of the newly founded Mining and Pastoral Association, and applied for and was granted the first of new squatting areas on the rugged and remote Evelyn Tableland, 60 kilometres from Atherton. These squatter’s blocks were for raising cattle, sheep and horses and Stubley sent a mining mate by the name of Willie Joss to manage “Evelyn Station”. By the mid-1880s the gold had all but disappeared from his once productive mines and Frank Stubley found he not only couldn’t afford his luxurious lifestyle, most of the people around him whom he thought were his friends had deserted him. He was no longer the life of the party and after losing his seat in Parliament, Frank became more and more disillusioned. He eventually started wandering around the outback towns hoping to find another Eldorado and was often seen humping his bluey with thousands of others who dreamed of what Frank Stubley had already won and lost.

DISCOVERED GOLD

It is not known if Stubley ever stayed to manage the 150 square miles of “Evelyn Station”, but Willie Joss is credited with having discovered gold at the headwaters of the Tully River in the area. If Frank Stubley had only known – his Eldorado had been in his own backyard all that time. But Frank Stubley didn’t know and one day in 1886, at the age of just 42, he was found dead and penniless along the track between Normanton and Croydon. He was buried where he lay. A man who had amassed a fortune of more than £300,000 (tens of millions in today’s currency) was simply another destitute gold seeker and nobody cared. The following appeared in the Warwick Examiner and Times of Wednesday, the 7th of April, 1886: Death of Mr Frank Stubley and Others from Heat Apoplexy. Writing of the late sudden deaths from heat apoplexy near Normanton, a correspondent to the Townsville Bulletin says: “We are now in the middle of March with every appearance of the dry weather continuing. The absence of rain causes the heat to be oppressive, and the result has been a number of sudden deaths lately from heat apoplexy. In most cases the constitution of the men whose deaths are recorded had been worn down by excessive drinking; but there have been exceptions to the rule, and even the strong and temperate have been stricken. Repeated wires coming in from Green Creek on Saturday, 6th instant, and Sunday, 7th instant, recording one death after another along the road to the Croydon, created some alarm in Normanton for a time, but when the particulars were ascertained the scare of an epidemic sweeping down upon the town disappeared; nor was there any reason to suspect that the blacks or anyone else bad poisoned the water holes along the road, as was also surmised.

The first death took place on the 3rd instant, about 40 miles above Normanton, the victim being John Thomas, usually known as Carriboo Jack, from his one time having had an hotel in Cooktown, called the “Carriboo Inn”. He was alone when he died, his mates having gone on before him to look for water. When the body was discovered it was swollen and discoloured, the swag being still strapped across the shoulders, and a piece of mosquito netting rolled round the head. The tracks about showed that the deceased had staggered like a drunken man for some time, and then fallen against a tree, injuring his head by the fall. The only valuables found on the body were nine shillings and sixpence in money, and a watch. The party who camo across the body buried it where it was, and afterwards reported the death to the police. On the following day, about five in the afternoon, Mr Stubley and two others had got as far as the Fifty-mile Lagoon, within ten miles of Green Creek, and they meant, after a short rest at the water hole, to go to the telegraph station that night. Stubley complained of not being well, but got on a horse to proceed, when he was noticed to lose the power of his hands, and was helped down. He then fell to the ground, complaining of his head, and in four minutes he was dead. This was the end of Frank Stubley, the successful reefer and member of Parliament, the wealthy squatter who went through two or three hundred thousand pounds in a few years, who came to Normanton almost a mendicant and died on the road to the Croydon, and there was buried.”

A pre-decimal bonanza

by Stick

I was spending the day out detecting with a relative, Eddie, who I hadn’t seen much of over the years. He was new to detecting and using a borrowed detector that I’d arranged for him. I wondered how the day was going to turn out because I had Eddie pegged as, well, not exactly a patient sort of fella and one who wouldn’t want to get his hands too dirty (he works in the IT industry). Nevertheless, I encouraged him to give it a go and tried to describe to him the great feeling you get when finding an old coin or relic and the thoughts that run through your head about who lost it, when and how. He was keen enough but after the first few sites I thought it was going to be a long day as we’d only spend half an hour at each spot before it was “there’s nothing here” and “where else can we go?” So, after several sites where I’d previously detected goodies were dismissed, I suggested to Eddie we try a spot of his choice. Being a local, he knew the area as well if not better than me, so he chose a location and you guessed it, after a short time detecting, it was declared another “nothing here” site.

WORTH A GO

We then retraced our steps and stopped at a site we’d passed on the way to Eddie’s spot, that smelled of possibilities. I was a little sceptical about it thinking others would have hammered the site over the years but we were in the area so I decided it was at least worth a go and Eddie agreed. It was an old high school that shut down in the 1970s but it had seen its share of students in the 50-odd years it had been operational. The grass out the front was now nothing more than weeds and prickles of almost every description and the ground was very hard, being mainly clay, which was understandable given the site’s proximity to the Murray River. After having a stroll around the buildings and a chat about this and that, we decided that out the front was the best place to begin our assault, so we geared up and set off in opposite directions to hopefully find some treasure. And what a surprise! I can honestly say I never thought a place like this, on a reasonably busy road, would have been left seemingly untouched or near enough to it given that metal detectors have been around for so many years. It was such an obvious site that everyone passing it must have thought it had been cleaned out years ago so they hadn’t bothered to give it a go. From the outset the coins started rolling in – a 3-inch-deep threepence here, a 5-inchdeep halfpenny there, another threepence this time two inches deep; mixed with a fair sprinkling of 1- and 2-cent coins, compass parts, scrap metal and so on. We were two very busy bunnies digging holes constantly.

The authors’ haul of pre-decimals from the old school site

There was so much ground to cover we knew we’d never get it done in a month of Sundays so we didn’t bother with gridding, which is generally a no-no when I go detecting. I like to be as thorough as possible even if I only cover a fraction of the ground. We just walked around wherever our feet took us and there were coins waiting. I’ve never been to a place like it, particularly for the pre-decimal coins which, while not being particularly valuable, were a thrill to find.

MOST SUCCESSFUL PRE-DECIMAL DAY

That day out with Eddie remains the most successful pre-decimal day I’ve ever experienced. In all, 49 old coins fell my way including 16 pennies and 14 sixpences, with a lesser amount going to Eddie but he still did exceptionally well for a newcomer with a machine totally foreign to him. I was elated for him. What a site to start metal detecting on. I only wish I’d been that lucky when I started out in the hobby. The oldest coin found on the day was an English halfpenny dated 1887. It was the only 1800s coin to come to light with the majority of finds being in the 1920 to 1960 range. The find of the day however was a superb florin dated 1910 which was a real bugger because it didn’t come to light under my coil. What can I say; beginner’s luck! At the end of the day the ratio of decimal to pre-decimal coins found was about 2:1 and most of the decimals were of the 1- and 2-cent variety. On average the finds ranged from 3cm to 15cm in depth, so basically any detector at all would have cleaned up. However, a few pennies were exceptionally deep. One I measured at just over 25cm down which proved quite an adventure to retrieve from the hard ground. As we were packing up to leave, the lady living in the house next door stopped by and told us there had been someone detecting on the site a while ago and they had found a nice signet ring. Evidently, she had been watching us all afternoon and wondered what we had been digging up given the fact others had been there before. She expressed amazement at the number of coins we’d retrieved.

BACK TO THE SITE

We’ve been back to the site a few times and have yet to come away empty-handed. The last time I was there I bumped into the groundsman who waters the weeds and prickles and he said he’d been over the site with a detector himself and only found nails and rubbish. Apparently, he had been looking for sprinkler outlets and said that if I could place a stick in any I located, he’d be grateful. I didn’t have the heart to tell him how much good stuff myself, Eddie, my brother-in-law; Darren, and his mate, Ricky, had pulled out of the site, let alone what other goodies the chap who found the signet ring had unearthed. My count alone now stands at 23 halfpennies, 35 pennies, 26 threepences, 27 sixpences, four shillings and two florins, totalling 117 pre-decimal coins. As well I have a large number of decimal coins, badges and other bits and pieces. It’s proved to be quite a patch and it isn’t cleaned out yet. I guess it goes to show that sometimes even the most obvious places still hold treasures, but you’ll never know until you get out and give them a go.

Capturing a northern goldfields Rhino

Early on a warm, sunny March morning my prospecting partner and I had returned to a regular spot where we’d enjoyed a growing success rate. We’d been chipping away for around three hours using our Minelab SDC2300s with no luck and having covered several kilometres on foot for no reward, we decided to pack up and move a little further away from what had become familiar ground. While scouting new terrain we found a huge horseshoe by the side of the road and took this as a sign our luck was about to change. It never hurts to be optimistic in this game. Soon after, we came across a new spot that really didn’t look anything special (although everything’s kind of special when you’re hunting for new ground). We decided to give it a bash anyway and drove on through a creek and up onto a small cleared area near several quartz outcroppings. We had a quick drink and a bite to eat before setting off in different directions. I went and detected the creek line while my partner detected around the bottom of the quartz lines draining into the creek, which was awash with leaves and sticks.

And on the scales. At the current gold price, you’re looking at more than $50,000

We’d been at it for about 15 minutes when I picked up a very strong signal at the base of an old, dead tree in the creek. Now, if anybody who has detected the northern goldfields knows, a hundred years of mining will give you a hundred years of rubbish, so, my first thought was that I’d found another debris-covered rusty relic. Putting my doubts aside, out came the scoop and removing about two inches of gravelly creek sand and crushed quartz revealed something a bit special. Keeping my composure, I called my partner over to “come and check out this old rusty can” “You should come over and see it before I break it up as it’s really quite old,” I said. Needless to say, she was reluctant at first because, hey, we’ve all seen a crappy old tin can before but true to her kind nature, she humoured me and came over to take a look. I moved away from the spot and pointed to where she should take a gander. She smiled patronisingly at me (as always) and moved carefully over to the tree base. She knelt down, cleared away a little dirt and then looked up at me with this dumbfounded look on her face. She let out a few words of excitement and then suggested I should dig it out myself seeing as I’d found it. After a quick little scratch, out came a sizeable nugget covered in dirt. A joyful jig then followed for the next 10 minutes before we settled down and set about thoroughly detecting the immediate surrounds. In fact, we spent the next two hours gridding and regridding the area and came up empty-handed. That was it for the day; exhausted but chuffed we packed up, drove the 50km back into town and treated ourselves to a pub counter lunch and a little refreshment or two. The SDC2300 is a great little detector having proved itself time and again. I highly recommend it and it lives right next to my new (and battle-scarred) GPX6000. Oh yeah, we called the nugget ‘Rhino’ because of its size and shape. It tipped the scales at 359.99 grams or 12.695oz.

A Rhino in the hand

Desperate remedies

Oddly enough, the greatest hazard facing gold diggers on the early goldfields, was not the threat posed by bushrangers but the conditions under which they lived. Life was incredibly harsh and coupled with the poor water supplies, lack of proper food and the primitive state of medical science, it’s a wonder more diggers didn’t perish. And, when illness did come knocking, more often than not the cure was worse than the ailment. There was no law preventing anyone setting himself up in practice as a “doctor” on the goldfields in these times. As a result, many “general practitioners” were not doctors at all but clerks or drapers’ assistants who pretended to be surgeons. Broken bones would be set without anaesthetic, while they would operate with the same knives that were used at other times to chop tobacco or spread butter. Doctors’ instruments looked like something out of a torture chamber, so it was small wonder the diggers tried to avoid doctors’ treatments where possible.

At the Forest Creek diggings at Mt Alexander (Castlemaine today) which in the 19th century was considered one of the richest goldfields in the world, many people died from dysentery, typhoid and chest complaints. Two hundred children died from the effects of polluted water, fouled with waste and mud. Although the Chinese brought in supplies of greens, the soil was so poor that the vegetables did not do well. After the Pennyweight Flat cemetery closed in 1857, an epidemic of influenza swept through the goldfield and there were many deaths that went unrecorded, but a year before, it appears that approximately 2,000 children under the age of 10 died in Victoria, many of them victims of the unhygienic conditions of the goldfields. And it was not only children who died.

Dr Williams’ “Pink Pills” were advertised as an iron-rich tonic for the blood and nerves to treat anaemia, clinical depression, poor appetite and lack of energy. The tablets were originally advertised as Pink Pills for Pale People. Users of the product claimed the pills could even cure paralysis!

In the case of one Bendigo man who had been shot through the neck in a fight, one doctor treated him by bandaging pieces of raw steak to his stomach. When this didn’t work, wine was poured into him and flowed out of the hole in his neck. Needless to say, the unfortunate digger died. Diggers who valued their lives treated their ailments with Holloway’s Pills, which contained opium. Extraordinary “miracle” cures were peddled in the 19th century, all with amazing claims. Although many had nothing much in the way of curative properties, doctors and hospitals were expensive and often none too reliable and these so-called tonics were widely used.

Beecham’s Pills claimed to cure practically every known ailment: “Constipation, headache, dizziness, swimming in the head, wind, pain andspasms in the stomach, pains in the back, restlessness, insomnia, indigestion, want of appetite, fullness after meals, vomiting, sickness in the stomach, bilious or liver complaints, sick headaches, cold chills, flushings of heat, lowness of spirits and all nervous afflictions, scurvy and scorbutic affections, pimples and blotches on the skin, bad legs, ulcers, wounds, maladies of indiscretion, kidney and urinary disorders and menstrual derangements.” The pills were said to contain “medicinal herbs” and they only cost a shilling a box for 56 pills. The medicinal herbs later proved to be aloes, ginger and soap. Dr William’s Pink Pills for Pale People were similar, claiming to heal most ailments from St Vitus Dance to rheumatism, and promising to create “rich red blood” which would tingle in the veins.

Gould’s Mutton Bird Oil claimed to cure wasting diseases. Holloways Ointment, already mentioned, claimed not only to cure dysentery but also “bad legs, wounds, piles, sores, eczema and all skin afflictions”. Besides opium, the medication contained. olive oil, lard, resin, white wax, yellow wax, turpentine and spermaceti. Positive thinking apparently did the rest. Captain Stringer and his “Jogga Wagga” healing waters were a different story. This cure was for malaria, syphilis and rheumatism, but when three people died after imbibing it, the liquid was analysed and it was found that the contents bore a resemblance to the water of the Yarra River, at the place where refuse from the gasworks mixed with that from the tannery! Similarly, Mrs Harle’s Pansy Packet or Towle’s Pills (which helped ladies cure all irregularities) could also cause death. Another medication called Peruna, which claimed to cure dyspepsia, enteritis, measles, colic, mumps, appendicitis and “women’s complaints” merely consisted of alcohol and flavoured water. Other medicines for children often contained morphine or opium, which could have serious consequences.

Always dreaming of an El Dorado

John Campbell Miles (Cam to his mates) was a dreamer. He dreamed he would make his fortune from gold. Like hundreds of miners, he dreamt that the next prospecting journey he went on would produce that elusive bounty. He was also a man of great courage and strength but, sadly, there is little recorded of the man who stumbled across a mineral field that made him famous and gave Queensland its richest mining city and thousands of people a living. Miles was the eighth of nine children born to a Victorian compositer and gold miner, Thomas Miles, and his wife Fanny Louisa (nee Chancellor) so “gold” was in his blood. Little is known of his childhood or education but stories from his father and swagmen who panned the creeks in the rainy season and only got a few ounces of dust, kept his dream alive. As he got older, he was lured time and again into the virgin bush, seeking his dream – a fabulous gold mine. In 1908, after having worked underground at Broken Hill for several months, he and a companion set out for The Oaks Goldfield in North Queensland, riding bicycles more than 2,490 kilometres through dust, mud, heat and desert to find that gold mine. It took them six weeks, and when they arrived, Miles became disillusioned. Two thousand gold diggers were already sweating away on a virtually worthless two square miles. The pair then decided to try their luck on the Etheridge field, and after selling their bikes for enough money to buy essential supplies, they set off to make their fortunes. After five weeks of back-breaking sweat and toil, all they found was three pennyweights of gold, and so fine it was like flour. This was not John Miles’s El Dorado and the two men parted company. Over the course of the next 10 years, Miles worked on stations, cutting sugar cane and prospecting. The dream of finding his golden fortune never left him. He had heard dozens of times an old stockman’s tale of the “richest run ofgold in the world” – a reef of gold and quartz which supposedly lay not far from the infamous Murranji Track, the Northern Territory cattle trail blazed in the 1880s. It was reputed to have claimed the lives of many men and cattle, and stretched across hundreds of miles of scrub and waterless plains.

In 1923, Miles set out once again and headed into the north-west area of Queensland. He was alone on this journey, except for his trusty stallion “Hard Times”, two foals, a mare and a pack horse. He paused beside the Leichhardt River after chasing the pack horse which had bolted on him suddenly. It had taken less than a minute to catch it, but it was crucial to do so as it had all his food and water on its back, and to lose it would have almost certainly meant death in this most inhospitable part of Australia. As he looked up at the surrounding low-lying hills, a glint caught his eye. Picking up his ferrier’s hammer, he walked towards the silver shaft of light. Upon reaching the overhanging rock, he brought his hammer down hard, and the rock smashed into a honeycombed pattern of black and grey. It was heavy too, and he realised he had unearthed a secret that the Earth had held for millions of years. He had learnt to recognise galena years earlier when he had worked at Broken Hill but this rock was different. After spending days collecting samples of the rock, he headed three miles east to the Native Bee, where four men were working the unprofitable mine. From here he sent 10 samples which he wrapped up and left beside the bush track for the mailman to collect on one of his infrequent trips to that area of the outback. They were on their way to the Government assayer in Cloncurry, 70 miles away. Miles waited patiently. Weeks later he received a letter to say that the samples, when analysed, showed that the poorest contained 49.3% lead and the richest 78.3%. The letter also said that he would be able to make a living out of mining this field.

John Campbell Miles, prospector and discoverer of Mount Isa, in August 1962, three years before his death

He then wrote a letter to his uncle in Melbourne, urging him to head north and help him mine this new field. He never received a reply. Miles was then joined by a red-bearded bushman, Bill Simpson, one of the miners at the Native Bee. It was these two men who pegged out the first leases on the Mt Isa field, and from which the milling city of Mt Isa came to be. Miles and Simpson pegged three areas of forty-two acres (17ha) around the original outcrops, soon known as the Black Star and Racecourse leases. Six months later the name, Mount Isa, was conferred on Miles’s find, by which time several consignments had been sent to Cloncurry, and much of the new field taken up. Already, however, the field’s future had passed into the hands of William Corbould who, with Douglas MacGilvray, had options over most of the leases, including those of Miles and Simpson. Mount Isa Mines Ltd was floated in January 1924; 12,250 shares of £20 each were allotted to the promoters to secure the optioned leases. Miles received 500 shares, nominally worth £10,000, some of which he sold over the following 20 months to sustain his prospecting at Lawn Hills. In December 1925, Miles still held 8,680 £1 shares; that had dwindled to 2,900 by 1929.

In 1930 he still had some money left and bought a “newfangled motor car” and once again set out on the Murranji Track to find the lost gold reef. But once again it was not to be. Nature intervened and sent torrents of tropical rain down, making the journey impossible. In 1933 he sold his last 400 shares. He returned to Mt Isa but stayed only a short time before returning to Victoria. Here he spent years fossicking for gold in the Gippsland area but all he ever found was enough colour to barely fill a small essence bottle. He spent the years up to 1957, wandering the goldfields searching for his El Dorado. The only two visits to Mt Isa after his discovery of the field in 1923, were in 1957 when he was invited to inspect the company’s huge mining and metallurigical operation, and 1962. It was probably characteristic of the wiry, weatherhardened prospector, whose only admitted vice was pipe-smoking, that he should return to the north-west overland by car, camping under the stars, and then accept accommodation only in the workers’ barracks. He never did regard his discovery as anything more than a stroke of good luck and was very pleased that it provided thousands of people with work, and a secure way of life. Miles never found his El Dorado. When he died on the 4th of December, 1965, at the age of 82, his ashes were taken back to Mt Isa and buried under the clock tower. Maybe, some day somebody will find that gold reef beside the Murranji Track, and John Campbell Miles will look down and smile upon them and know that at least for someone, his El Dorado dream came true.

More lost treasures

By Jackal

The hills of South Gippsland have been attracting treasure hunters for more than a century, with the coastline and countryside around the small town of Inverloch the focal point. First there was the search for thousands of gold sovereigns stolen by Martin Weiberg (also Wiberg) from the S.S. Avoca in 1877 and believed by many to still lie hidden in dense scrub close to the town. Weiberg, the ship’s carpenter, stole 5,000 coins from the strongroom then left the sea shortly after and settled on the Tarwin River near Inverloch. When a young girl employed by Weiberg found a large number of sovereigns hidden in bars of soap, she notified the police who had been suspicious of Weiberg but lacked proof Weiberg was arrested and after volunteering to show where he had hidden about 1,700 of the coins, escaped into the bush and remained at large for about five months before being recaptured in May 1879. He was tried and sentenced to five year’s imprisonment. Weiberg was released on the 4th of June, 1883, and from this point his movements are shrouded in mystery. One story claims he was drowned while attempting to row out to a yacht anchored in Waratah Bay; another says he escaped to Europe with the remaining sovereigns and finished his days as a successful businessman. The search for his treasure has attracted a great deal of publicity over the years but an even more valuable hoard supposedly smuggled out of China by opium trader John Nicholson, has escaped notice.

Nicholson’s grandson, Donald, started searching for the treasure, reputedly gold and jewels, at Screw Creek on the outskirts of the town in 1939, and the early in 1940, the Australian Army supplied 12 men to help him survey and dig into the hillside. A vault with an armed guard had even been prepared at the Commonwealth Bank at Melbourne to take the treasure, however the Army withdrew its men, which probably had something to do with the Second World War getting underway! Donald Nicholson remained on the banks of Screw Creek, which winds through dense scrub to the sea at Andersons Inlet, and when he died in 1954, the search was continued by his widow and two other elderly women. When asked why his grandfather didn’t pass on the exact location of the treasure, which grew over the years from 10,000 sovereigns to gold and jewels worth £200 million, Nicholson claimed he was a Presbyterian lay preacher in his younger days but when he changed his faith and joined the Seventh Day Adventists, the family disowned him.

Subsequently he returned to the Presbyterian Church and his father, who apparently had been shown the site, was on his way to Inverloch from Western Australia in 1940 when he dropped dead. Although Donald Nicholson never discovered the secret site, he firmly believed the story of the vast fortune right to the end. And the story was this: John Nicholson was a wealthy shipper in the late 1800s. He and three other Australians smuggled food to China during an internal struggle for power there and were paid in gold. When the Chinese ran out of sovereigns, they began paying with jewels looted from temples.

An illustration of Martin Weiberg’s escape from police. (State Library of Victoria)

When the food running ceased, the fortune was locked in a steel vault buried in the hill at Inverloch. One by one the partners died, finally leaving John Nicholson as the sole guardian of the fortune. Before he died, John Nicholson told his son the money was not to be touched until young Don, then only a lad, reached 21. If the father died before Don’s 21st birthday, the money was his. When Don Nicholson was 20, he quarrelled with his father who told him to find the treasure himself. Since the 1950s, several syndicates have continued the search, all without success. Stories of hidden treasure near Inverloch do not end there. In 1984 a few local enthusiasts conducted a clandestine hunt for bullion supposedly buried on Townsend Bluff, the headland overlooking Anderson Inlet. They were so confident of success that representatives were sent to Melbourne to negotiate a deal over its ownership with the State Government. Nothing ever came of the venture, at least nothing that was made public.

Seeds of suspicion at Southport

By Barrack

The Northern Territory gold rush of 1873 saw diggers pour into the fields from the goldfields of Queensland, and with them came the inevitable spate of crimes and misdemeanours. As claims dried up, many of the diggers moved on but scores stayed and the opening up of grog shanties and the continuing lawlessness made it necessary for the Chief of Police, Inspector Paul Foelsche, to set up a police station at Southport. This small community, 25 miles south of Darwin, was one of the wildest places close to the diggings and men bound for the goldfields loaded up their supplies from here. Southport was wild and woolly squalid and untidy. And then one day Southport policeman, Mounted Constable Edwin Ferguson, reported that 202 ounces of gold to the value £740 had been stolen from the safe at the Post Office on the night of the 8th of July, 1880. Inspector Foelsche sent one of his best men, Senior Constable Becker, to investigate this matter. On arrival, the postmaster, Joseph Johnson, informed the Senior Constable that five parcels of gold he had placed in the safe the night before, were missing when he opened up the office the next morning. He explained that he’d found the key to the safe still in the lock, but the door was unlocked. Mounted Constable Ferguson had searched the quarters of the Chinese cook, who had a key to the office but not to the safe; the quarters of the office keeper and the nearby Chinese market gardeners, all of whom he said he suspected. He had also made a thorough search of the surrounding area and found the wrappings from the parcels of gold in an unoccupied store near the market gardeners’ quarters behind the Post Office.

The Estelle moored at Southport short quay on the Blackmore River in 1876. The photograph was possibly taken by Inspector Paul Foelsche. Southport was a thriving river port during the Pine Creek gold rush of the 1870s

A WATCH ON THE CHINESE

It was decided to keep a watch on the Chinese and Becker and Ferguson did just that until 10pm, when Becker told Ferguson to turn in as he would wait a while longer. An hour later Becker heard the police station door open and wondered if his suspicions about Ferguson were correct. Since his arrival in Southport the Senior Constable had harboured serious doubts about the integrity of his colleague. Becker challenged Ferguson next morning and the latter hesitated and then admitted that he had left the police station after supposedly retiring, to have another look at the Chinese. Becker was not satisfied but he had no concrete evidence on Ferguson and told him to take the natives and keep searching for any more evidence. More wrappers and papers were conveniently found in a hole and Becker’s suspicions deepened. As a pretext to get Ferguson out of the way, Becker sent him off to Darwin with the Chinese whom Ferguson had by now arrested for the gold robbery This gave the Senior Constable time to search Ferguson’s quarters. After a 3-hour struggle with a strong box and eventually finding the key to this box in another box, Becker opened it to find the parcels of gold along with a corked bottle. Senior Constable Becker summarily arrested Ferguson who, for some unexplained reason, had not left the town. The Chinese were released and Ferguson stood in the dock eight days later before two Justices of the Peace, charged with stealing gold to the value of £740 pounds. Ferguson’s only defence was that he claimed he had brought 800 gold sovereigns to the Territory when he had first arrived however this didn’t explain how they had somehow turned into unminted gold and what was the story regarding the corked bottle, which looked as if it contained gold too? He was ordered to stand trial at the next sitting of the Circuit Court in Darwin.

STEALING A FURTHER 23 OUNCES

Then, on information from Inspector Paul Foelsche, Ferguson was charged on the 7th of August, 1880, with stealing a further 23 ounces of gold, the property of former Mounted Constable A. A. Fopp. The contents of the corked bottle were indeed gold! Ferguson then lamely told Becker he had merely been looking after the bottle while Fopp was away in Adelaide. But this was not the end of the transgressions of the now demounted constable. Further information from the Inspector, this time to do with Inspector Foelsche himself, led to Ferguson being charged on a different writ on the 20th of September, 1880. This offence happened before the gold robbery. Inspector Foelsche had advanced monies to Ferguson to recompense him for fees paid for the burial of a Chinese but no such burial had taken place. On the 1st of May, 1880, Ferguson was charged “that he obtained a money order for four pounds with intent to defraud Her Majesty’s Government.” It seems Ferguson had been busy with this particular vice long before the gold robberies. Four other cases of a similar nature all relating to the interment of departed Celestials, were afterwards disposed of and the prisoner was committed for trial on each count, so said the North Territory Times and the Government Gazette. The trial of Edwin Ferguson, former Mounted Constable, was held at the Circuit Court in Darwin on the 23rd of September, 1880. He was found guilty on all counts with sentences to be served concurrently – gold stealing, seven years imprisonment with hard labour; theft of a bottle of gold, two years; and for obtaining money under false pretences, he got three years.

Inspector Paul Foelsche, Chief of Police of the Northern Territory. Foelsche was an avid amateur photographer but his treatment of Aborigines, while lauded by some, is regarded by others as abhorrent and a black mark against a succession of South Australian administrations

Handy gold prospecting hints

By JMcJ

THE PATHFINDERS TO GOLD

Many prospectors will give country consisting of limey rocks a miss if they’re looking for gold but don’t you do it. Limey rocks can be the host of disseminated gold deposits. While such deposits may not be of much value to the individual, a mining company would certainly find them very interesting! A disseminated deposit is one that is scattered, a bit like micron-sized wheat that’s been cast about. You may not even see the gold in such deposits but you can test for it. A lack of visible gold at grass roots level shouldn’t mean much to a prospector that knows his or her stuff. A good prospector has an “earth map” and by that I mean they have the knowledge of and can recognise minerals that are pathfinders to gold. Arsenic, stibnite, cinnabar, scheelite and so on are all indicators that gold could be in the vicinity. A good prospector also won’t ignore zones of silification in sediments (brecciation, jasperoids etc) also acid volcanics. Learn as much as you can about such minerals and the type of country in which they’re found. Only time and experience will teach you the craft. You don’t need a degree in geology although a little geology acquired in the field certainly helps.

OPEN YOUR EYES AND YOUR MIND

In open country I have always been one for getting up on an open-topped knob and spending time with a pair of binoculars, a map, compass, notebook and pen. I study the country about me, taking it in until I form a picture of how it once was, what happened in between and how it looks today. I could write a whole article on this but let me just say that I look for rock features that might be conducive to my quest. I look for colour changes in rocks of the same type, and for changes in rock types. I also look at soil colours including what is evident in ant hills (the great Gove bauxite field was prospected after its red ant hills were spotted from the air). Vegetation is also important. A lack of or abundance of plant life can tell you many things. I next enter onto the map what I find at my marked points and in time these things form a picture. It may not be a clear picture at once but the more time you put into your study the clearer the picture becomes. But remember that you must always be flexible. The map you have made might work very well in the area you have charted but the same conditions encountered elsewhere could present you with an entirely different set of possibilities.

THE NUGGET PUZZLE

Nuggets of gold, true nuggets, pose a bit of a puzzle as to how they came to be where they are. They may be as smooth as a baby’s bottom, as if they had just been plucked from a river, yet be found in country that sees only a couple of drops of rain every fifty odd years. You will not find a true nugget in a reef, specimens yes but nuggets, no. You will find nuggets on the paddock but rarely more than a little distance below it. Only on a small number of fields will you find patches of nuggets and fine gold together. On some mining fields you will find nuggets in the gullies and not on the flats, while the reverse also occurs, which flies in the face of the theory that gold will always work its way to the lowest points in any area. In New Guinea I picked up nuggets high on a terrace when so-called logic said they should have been washed down into the gully below. Gold nuggets certainly are strange creatures and while all sorts of theories have been tossed into the ring, don’t let anyone fool you into believing they know the answer to the question of how gold nuggets end up being where they are found.

LOOK PAST THE JUNK

If you dig a piece of junk such as a nail or horseshoe, don’t just fill in the hole and move on, but run your detector over the hole again. I once saw a nice fourounce pancake nugget taken from below a horseshoe and I picked up a 20-gram slug from beneath a section of heavy iron plate that was visible to the naked eye. Incidentally, when you find junk, do yourself and others a favour and take it with you when you leave.

LOOK TO YOUR ROOTS

If you ever encounter a great old riverbank tree that has been uprooted in a flood or gale, never ignore it if the creek or river nearby carried gold. The tree’s root system will hold plenty of rocks, pebbles, sand, silt and clay and very likely gold. And if the tree came from the inside of the waterway’s bend, where the water runs slowest, it’s almost certain you’ll score some nuggets.

A TIP FOR WEIGHT WATCHERS

Long ago a prospector who had spent many years in South Africa told me of a blind native who picked through old mine heaps. If he picked up a rock that contained gold, he knew so by its weight. Many times I’ve picked up a lump of quartz that seemed to be too heavy for its size but I couldn’t see any gold. These lumps also tested negative with the detector and even on inspection with a hand lens, I couldn’t see anything. But, after crushing the lumps to dust and dishing, there was the yellow stuff. Quartz is about seven times lighter than gold so a few grams of gold added to a fist-sized lump lets you know it.

In search of lost treasures

By TP

There are at least 5,000 known ships (not all treasure ships) wrecked around the Australian coastline and probably a very large number of ships met the same fate before Australia was colonised. Ships foundered on Australian reefs, islands, and the coast, well before Captain Cook sailed up the east coast of Australia in 1770. The Dutch treasure ships Batavia, Gilt Dragon, Zuytdorp and Zeewyck had already come to grief off the Western Australian coast. It is generally accepted that the Spanish, Portuguese and Dutch knew of Australia and visited its northern shores centuries ago. Items have been found to tease the historians and in some cases, they have wondered if the items found were brought here by the original owners or whether a collector carelessly dropped or lost the article. A coin was once dug up at Cairns and created a flurry of interest as it bore the stamp of Ptolemy IV, who supposedly ruled Egypt more than 2,000 years ago. Torres Strait Islanders once practised the art of embalming their dead. They then took the mummy to sea in a canoe and this is a similar ritual found in Egyptian mythology.

UNEARTHED AT ROCKHAMPTON